Forms of Attachment, from the series Monument for Feeling, 2021. Inkjet prints. 30 x 40 inches each.

Melissa Weiss

BIO

Melissa Weiss is an artist, designer, and educator. She is an art director for Verso Books and a Visiting Designer at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

ARTIST STATEMENT

In one of her poems, my maternal grandmother Ani writes “You still have a future / even with such a past.” A “future,” she insists, is still possible, even as it hinges, precariously, on everything that came before it. My grandparents rarely spoke about the war but they left behind an archive of documents, letters, and photographs that point back to their experiences. Through my ongoing project, Monument for Feeling, I explore my relationship to my family’s past by giving expression to the questions that live within and between the objects in our archive.

Interview with Melissa Weiss

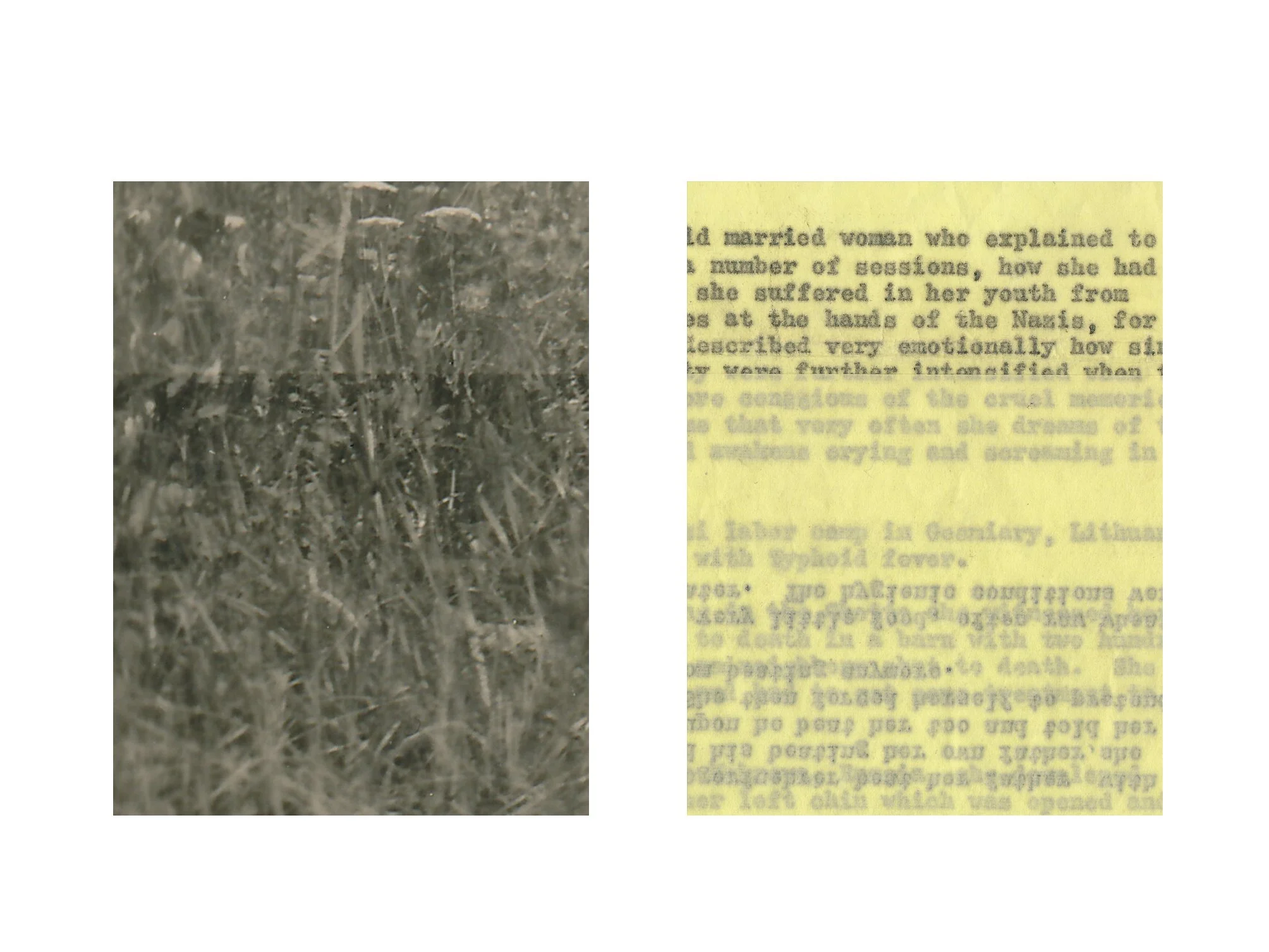

To Whom it May Concern, diptych from the series Monument for Feeling, 2021. Inkjet prints. 30 x 40 inches each.

Can you tell us a bit about your background and how you became interested in becoming an artist? Who or what were some of your most important early influences? Any stories you can share about early memories of how an aspect of the arts impacted you?

I’ve always had a creative practice but didn’t identify as an artist until more recently. Something important shifted when I finally gave myself permission to think about my family’s past—and to wrestle with it. All of my grandparents were Holocaust survivors but rarely spoke about their experiences. Growing up, I was afraid of looking at my family’s history too closely, of feeling too much. In retrospect, I think that fear of looking backwards, which I carried with me for nearly 30 years, prevented me from recognizing the fragmented memories I had inherited from my grandparents for what they are: an integral part of who I am.

Where are you currently based and what initially brought you there? Are there any aspects of this specific location or community that have inspired your work?

In the summer of 2020, I moved to the Midwest to teach at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Those were still the early months of the pandemic. Everything was shut down and everyone shut in. Since I couldn’t get to know the city that I had moved to, I got to know Lake Michigan instead. I walked to the shoreline every day and took a photograph of the horizon. I was in an unfamiliar landscape but liked knowing that the lake was a place that I shared in common with my grandparents, all of whom moved to Chicago as refugees. In that endless field of blue (or gray or green, depending on the light) I found a connection to the past and the present—a place to return to and to think from.

Can you describe your studio space? What are some of the most crucial aspects of a studio that make it functional? Do any of these specific aspects directly affect your work?

My studio is small and most of the space is occupied by a large wooden table—the anchor for my art practice, design practice, and, during the pandemic, remote teaching practice. I’m often shifting back and forth between digital and physical projects and having a large surface to work and think across feels essential.

What is a typical day like? If you don't have a typical day, what is an ideal day?

An ideal day starts with an early morning swim in Lake Michigan and ends with a walk in the woods. Starting and ending the day in such a way makes everything in-between (the stuff that pays the rent) more tolerable and sometimes, as if by diffusion, even pleasurable.

What gets you in a creative groove or flow? Are snacks involved? ☺ Is there anything that interrupts and stagnates your creative energy?

As an educator and designer, I find time for my art practice in the cracks between classes and clients and commutes. Finding time to slow down is my biggest challenge and the single-most important condition for making work that feels meaningful.

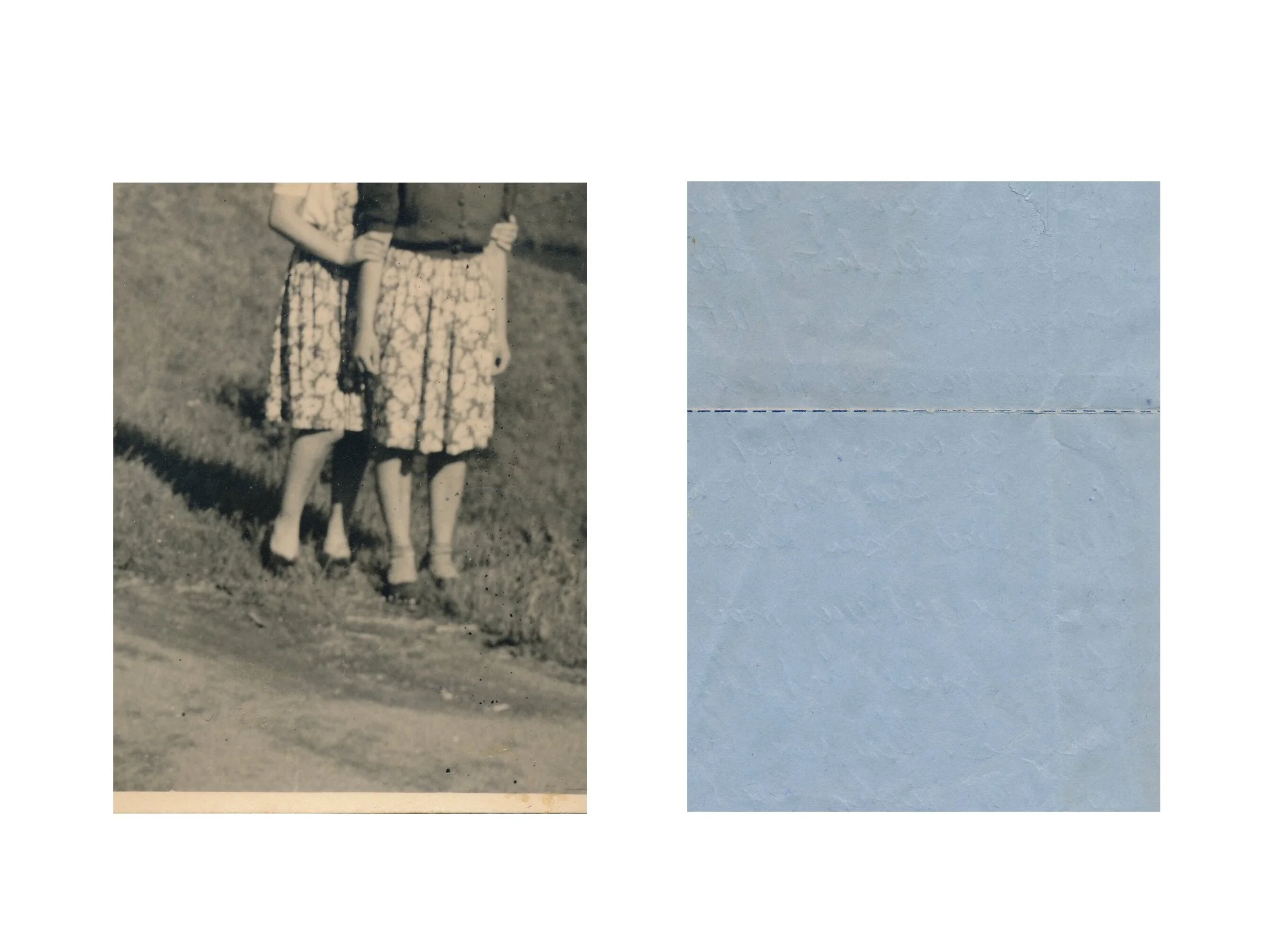

Sisters II, diptych from the series Monumet for Feeling, 2021. Inkjet prints. 30 x 40 inches.

How do you select materials? How long have you worked with this particular media or method?

I was introduced to the darkroom in high school but started working with archival photographs and objects much more recently. I don’t think of the material that I’m working with as a collection of objects but instead, a series of insistent questions that need my attention.

Can you walk us through your overall process? How long has this approach been a part of your practice?

In “Excavation and Memory,” Walter Benjamin beautifully writes, “He who seeks to approach his own buried past must conduct himself like a man digging. Above all, he must not be afraid to return again and again to the same matter; to scatter it as one scatters earth, to turn it over as one turns over soil. For the “matter itself” is no more than the strata which yield those images that, severed from all earlier associations, reside as treasure in the sober rooms of our later insights.”

My process and practice is rooted in this act of returning again and again to the same material—in finding and giving expression to the questions that live within and between the objects in my family’s archive.

Can you talk about some of the ongoing interests, imagery, and concepts that have informed your process and body of work over time? How do you anticipate your work progressing in the future?

In 1951, my maternal grandmother Ani wrote “You still have a future / even with such a past.” A “future,” she insists in her poem, is still possible, even as it hinges, precariously, on everything that came before it. Like all of my grandparents, Ani was a Holocaust survivor. For her, the future was, for much of her young life, an unlikely destination that lay beyond the gates of the concentration camp, Dachau.

Lately, I find myself circling back to my grandmother’s words. She seems to be reminding herself: you, in the present tense, in 1951, are inseparable from the yous of your past and the yous of your future. To deny one part of yourself, is to disregard yourself all together.

There is a way in which time itself collapses in the poem fragment. The “you” is presumably self-referential—a you belonging to my grandmother—but the word structure also allows the “you” to belong to me, three generations later. I have a future, my grandmother reminds me—not just in spite of the past—but because of it. In this sense, even the most unspeakable past, contains within it, a future tense.

I think my grandmother understood that hope, if such a state was possible, would need to be composed, in part, of the sorrow and loss that had proceeded it. And three generations later, I see the archive as a possible location for hope—a site from which all of the tenses can be accessed simultaneously—a place to look back from, a place to attend to the present, and a place to feel into the future.

What, I wonder, are the possibilities that emerge out of looking closely at the past, but from a distance? Some things are hard to decipher and impossible to resolve from where I stand. But in another respect, I think the field of view widens with distance, allowing for a different way of looking—and maybe even, the possibility of seeing something new.

Sisters, diptych from the series Monument for Feeling, 2021. Inkjet prints. 30 x 40 inches each.

Do you pursue any collaborations, projects, or careers in addition to your studio practice? If so, can you tell us more about those projects, and are there connections between your studio practice and these endeavors?

Since 2018, I’ve been an art director at Verso Books. As an English major gone astray, books have always been an important part of my life. When we open a book that changes the way we see the world, it’s transformative—the best books, like the best art, function like future artifacts, pointing insistently toward new ways of moving and thinking through the world.

The anthropologist Gregory Bateson beautifully refers to “the contemporary ecology of ideas”—a boundless network of thinking from which meaningful change is realized. He writes “The very meaning of “survival” becomes different when we stop talking about the survival of something bounded by the skin and start to think of the survival of the system of ideas in a circuit.” I see my work with Verso—and my work as an artist and educator—as different ways of contributing to that rhizomatic network of ideas.

Have you had any epiphanies recently that have changed the course of your work or caused you to shift directions?

Moving to Chicago, where my grandparents found refuge after the war, has been a provocation. I’ve moved many times but have never been so curious about how one develops a sense of place and, more specifically, what constitutes “home” for displaced people and the generations that follow.

As a result of the pandemic, many artists have experienced limited access to their studios or loss of exhibitions, income, or other opportunities. Has your way of working (or not working) shifted significantly during this time? Are there unexpected insights or particular challenges you’ve experienced?

Teaching remotely was a challenge but my students were a constant source of inspiration. I am still in awe of their ability to navigate such an uncertain time—and so many obstacles—with grace, patience, and perseverance.

Traces, diptych from the series Monument for Feeling, 2021. Inkjet prints. 30 x 40 inches each.

Can you share some of your recent influences? Are there specific works—from visual art, literature, film, or music—that are important to you?

A few years ago, I was introduced to the work of the late theorist José Esteban Muñoz. For Muñoz, hope was “both a critical affect and a methodology.” In Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, he wrote that it is essential to have the critical space to imagine and perform the “should be” of utopia, which stands against “capitalism’s ever expanding and exhausting force field of how things ‘are and will be.’” Like many artists, I’ve always found a “critical space” in creative practice—but it was Muñoz who reminded me how important it is to find hope there as well.

Who are some contemporary artists you’re excited about? What are the best exhibitions you’ve seen in recent memory and why do they stand out?

I spend a lot of time thinking about the work of Walid Raad. Taryn Simon, Do Ho Suh, and Francis Alÿs—artists whose work asks, albeit in very different ways, how we remember and draw meaning from personal and shared histories.

What are you working on in the studio right now? What’s coming up next for you?

After a six-year pause, I recently returned to the ceramics studio. I’m interested in using clay—a material derived from place—to continue exploring my relationship to “home.”