Casual portrait of Gil Rocha

Gil Rocha

Gil Rocha was born and raised in Laredo, Texas. He earned a BFA from the University of Texas in San Antonio (1999) and MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (2006). His work was part of two major Texas exhibitions: the Texas Biennial (2017) in Austin, TX and the Trans-Border Biennial (2018) held at the El Paso Museum of Art and El Museo de Arte en Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. He also guest-curated Mexic-Arte Museum’s exhibition “Young Latino Artists 23” in Austin, TX in 2018. He is the painting and drawing instructor at The Vidal M. Treviño School of Communication and Fine Arts, Board Member of the Laredo Center for the Arts, and committee member of the Laredo Culture District Project. Currently, he is curating an exhibition to coincide with “The Other Border Wall Project” at the 937 Gallery in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and preparing for his solo exhibition at the Presa House Gallery in San Antonio, TX.

Interview with Gil Rocha

Questions by Nancy Kim

Your latest work focuses on life at the US-Mexico border where you grew up and currently live. Gil, can you give us a bit of background about Laredo, Texas? How has Laredo and Nuevo Laredo across the border changed as you’ve grown up? What was it like growing up in a border town?

Growing up in Laredo and Nuevo Laredo was so much fun when I was young. These cities' combined populations are well over half a million people. Divided by the Rio Grande, this border is ranked as the number one inland port of entry into the United States. Always populated with trailer trucks and heat scorching temperatures reaching 110-115 Fahrenheit during summer days, this border is filled with never ending stories of hardship and hard work.

During my childhood I had family on both sides of the border. Most family gatherings happened in Nuevo Laredo. Going to the corner store to pick up a six pack of beer and cigarettes for my uncle, was no big deal; unlike the U.S.A. Traces of the ranch life followed the outskirts of the neighborhood, where one maternal grandmother lived. It wasn’t uncommon to have chickens in your backyard and take showers from buckets with cold water. I never saw the struggles, because there was always food on the table and my family was very close.

As I got older, still in my teens (14/15), I started hanging out with high school friends who had homes on both sides of the border. At that time, I saw another side of Nuevo Laredo. We began to attend “Quinceañeras” (15th birthday celebration for girls), house parties, nightclubs and brothels. The nightlife was a fascinating world that was nothing I had experienced before. It was filled with alcohol, women, music, lights, and all at a very cheap price. Tourists would migrate by the hundreds to take part of the splendors Mexico provided. The Mexican police were easy to bribe and made it almost encouraging to see what one could get away with. All in all, there was what seemed to be a silent, but understood rule, “don’t fuck with the wrong people”. And by the wrong people, it meant the “Narcos”.

Narcos were easy to regognize because they had an attitude of “dont fuck with me”, surrounded by tough guys and always dressed nice. We would acknowledge their presence to show respect and simply move along to avoid any confrontation. There were some unfortunate occasions where we had to fight or run from them, but those are other stories I rather not talk about.

Everything was “safe” up until August 1, 2003. This day marked the end and beginning of a new era; an era where all hell broke loose. A narco turf war began and continues until this day where thousands of people have been murdered; including many innocent. The Mexican side of the border is unsafe, even though it is policed by the Mexican military and there are hundreds if not thousands of people from different nationalities including Africa and Cuba, waiting to cross in search of the American dream. But as of now, and with all these unfortunate changes, Laredo continues to be safe, but still not as fun as Nuevo Laredo once used to be. Tear!

Attached are links to the actual story and a video of the night of August 1, 2003.

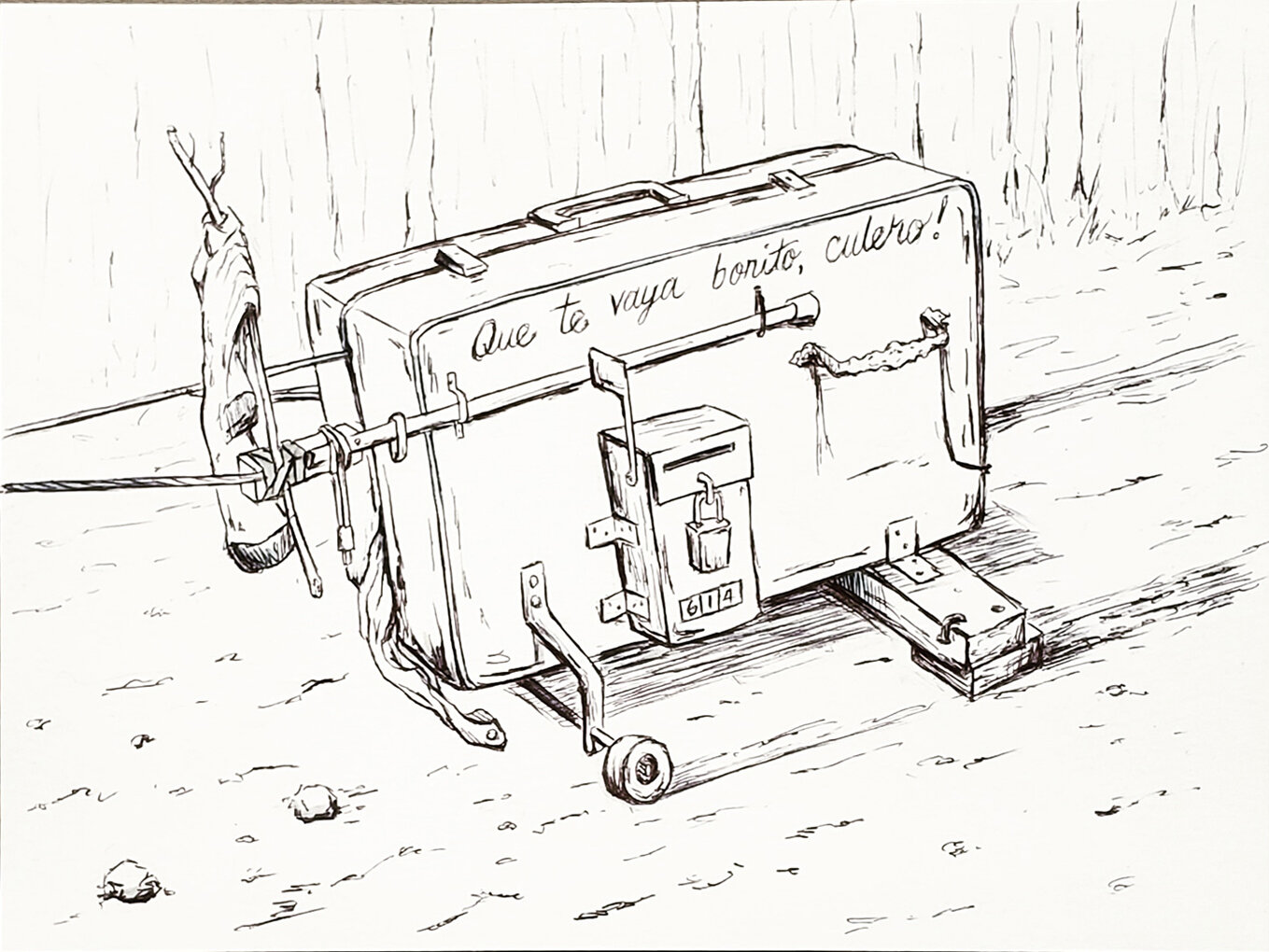

The Silence on Border Mint, 2017. Mixed Media, 1.5 × 1.5 × 3 feet.

Listening to you and going through your links, we can see that these are such complicated issues with a lot of moving parts that affect people in very real and profound ways. In your work, you do not shy away from these issues, but rather, foreground everyday people living with these big, pressing issues as the backdrop. I think about your “Carritos” works that show sculptures/plans for sculptures that reference carts and truck beds piled with objects to be taken over the border. The different carts seem to represent a different situation of crossing. For example, The Silence of Border Mint, was inspired by ladies bringing stuff back and forth across the border, and uses a small metal cart that you might often see people using to pick up stuff from the grocery store. It’s an everyday kind of cart for short back and forth type trips, but the items inside reference, directly and symbolically, border crossing and the violence in Nuevo Laredo. Can you talk about how this piece came about? How do you select what goes in the carts? Who are these ladies that inspired the work?

The common ground between The Silence of Border Mint and other works in this series, is the idea of carrying things. Not just the things we carry physically, but also those that we carry emotionally. You mentioned something very important that lays a platform for a lot of these works; “pressing issues as the backdrop.'' Primal instincts of survival have led me to think of scenarios which I could potentially face or other people have to, when crossing the border. It is very unsettling, but I can’t help to think about it, it’s always in the back of my mind. Unintentionally, threads of “violence” and “protection” have become more apparent throughout my work.

This work for example, started as a fictional lady crossing back into Mexico and I asked myself, “What things could she be carrying?” I initially started by collecting items with a mint color and arranged them to see how they would speak to me as a group. After a few days of rearranging things, everything took a drastic turn when I took a Mexican newspaper with a photograph of horrendous murder scene in the front page and in it, layed a young drug dealer laying over a pool of blood. In bold letters the headline read “Granadazos y Cuernazos” (translates to “Grenades and Huge Horns”). The “Huge Horns” was actually making reference to the AK-47 assault rifle which is often nicknamed, “Cuerno de Chivo” (trans. Goat Horn). Language can become very poetic in the border, where some things stand for others and images blur in translation. This young man had been murdered and left on the street with his mouth wide open. A series of connections ran through my mind as levels of interpretation began to develop with this impacting image. In the studio, it must have been hours, but felt very immediate in how the piece came together. I took an old Mexican wooden mask of a hyena-like creature missing both ears and with its mouth open as if it’s laughing and laid it over a folded pillow. I tied everything together with a thin red rope and attached a horn I fortunately had laying around in my studio. When I stepped back the work spoke to me visually and conceptually. It had become very unsettling.

The mint colored cleaning items contrasting against the saturated reds of a murder scene really stood out. The traumatizing look of a lifeless figure, next to a mask held down over a pillow, insinuated a nightmare taking a physical form, and to top it all up, deep under everything lays a doll, buried upside down, as if innocence is now dead. The piece makes me uncomfortable and as the days go by, continues to do so more and more, considering how we are becoming less safe in the United States due to random acts of homeland terrorism.

The Silence of Border Mint holds such latent violence and yet the colors are so bright, almost cheerful. And with other works in Carritos as well, the colors are happy and the aesthetic is kind of light and at times cartoonish. There seems to be humor to them. I don’t want to say funny, because it doesn’t feel like a joke, it’s not sarcastic...it’s more like a contrasting lightness or a breeziness? A breeziness that sparks the imagination? What role does humor play in your work?

I love humor. I love stand up comedy, especially when there's dark humor involved. Many things I keep to myself, but deep inside I’m laughing while thinking “I know I’m going to hell for laughing at this.” I don’t really think of my work as humorous, but I guess they can be. I’d like to think that the approach I take to express what I wish, does take a light sided angle, like in comedy. Sometimes I lure the viewer with colors and the familiarity of objects, but after careful observation they may find a side that is much richer in content. Maybe my work is like a Mexican candy that has a really colorful package, but once you try, it’s sour and very spicy.

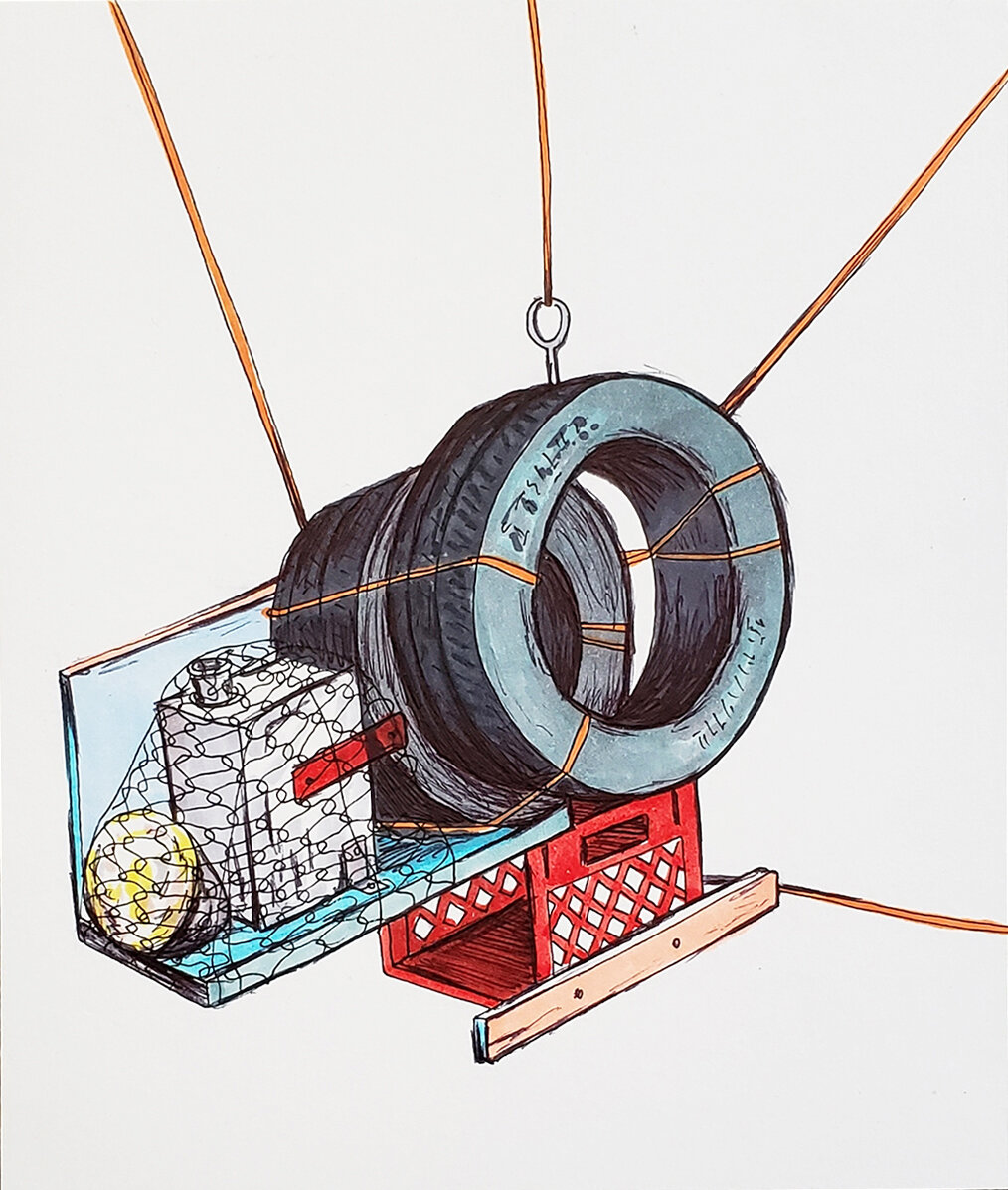

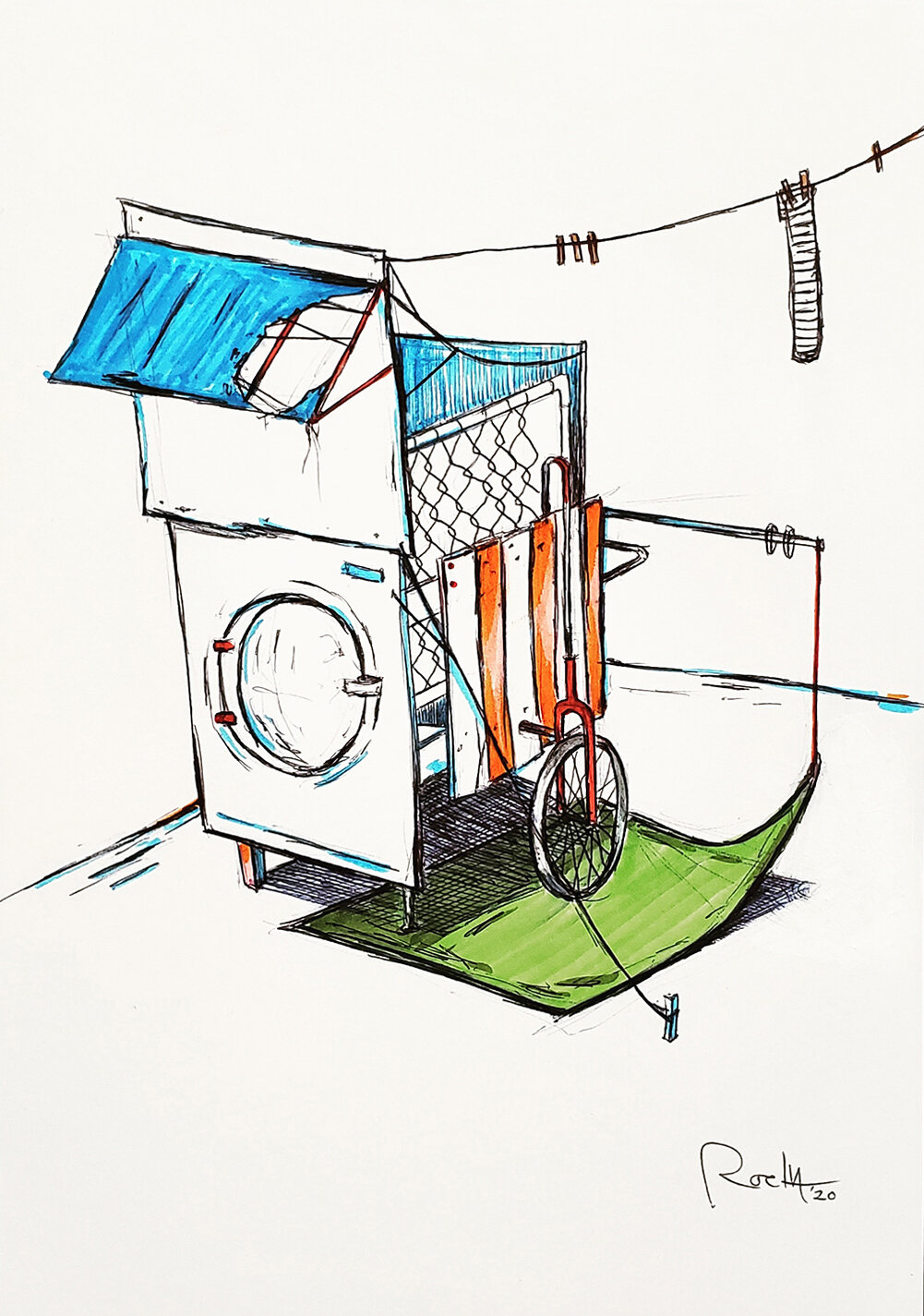

It looks also like the idea of carrying loads are manifested in many ways through different functionalities and realized in different media. Pescando una peda is a crate carrying fishing equipment attached to a wheelbarrow-type wheel with bicycle handlebars, suggesting both providing for survival and leisure on the cheap. Untitled seems to be a slap-dashed clothes washing station fashioned into a cart that is ready for business. C is for... carries an emotional/psychological weight with its sign/ladder made from found wood, embedded text, and objects that act as symbols of desire for betterment and the inherent obstacles. When I look at these pieces, my mind wants to make stories about who these carts belong to and why they made them. I see them as clever, ingenious spirits who find moments of grace inside of struggle. When you are creating these pieces, do you create characters or stories? How important are stories?

Yes, all these pieces have the idea of carrying things in common. I think these objects have their own characteristics from being worn out; each has a story. They, to me, are like words and when put together have the power to tell a new story. I do try to envision a certain persona when creating these works. And even though they are very specific, I wish to think that it would be someone who doesn't have it easy. I think of them as if they continue to be worked on by the person pushing, pulling, or carrying them. They are in a way portraits left to the imagination.

I don’t follow a particular formula. Many times I write more than I make art, and ideas lead to stories and characters, but at the end, the work has to have everything and look effortless. I work very hard to take out the fluff and make many of these pieces as if they were found just the way you see them. Once I start working, I let go and simply follow the route the work wants to go in. Because of this, there are many failures, but when everything works, it’s such a great feeling. I love when I hate it. It becomes its own thing, with its own stories and consequently it makes me reinterpret how I view other works and things in life.

“I love when I hate it.” I really respond to that comment, and it feels very Gil to me. I’m really interested in how we decide whether our works are successes or failures. Can you talk more about that? When something works, do you know right away or does it take time? Is there a list of mental criteria or is it more from the gut? What is a success and what is a failure? What do you do with your “failures”?

Many works are left unfinished for a number of reasons. I think in many cases it is because the essence of the idea wants to embody a different form. With the “failures” they are eventually tossed into the trash. There is little balance of both mental criteria and gut/intuition. Loving when I hate it doesn’t happen often. Those are pieces that become breakthrough moments. Pieces that will look very similar to the previous or next, but in the mind, things have taken a new direction. Again, that direction is led by the work itself. Many do start directly from sketches, but with nothing set in stone.

Maybe this can explain it better:

In the studio: Working on several works at the same time, with notes, sketches and scattered pieces here and there throughout the studio.

Me to the work: “Well, things are coming along quite well, how are you feeling?”

Work / Intuition: “I feel very predictable, you suck!”

Me: “Well fuck you! What do you mean by very predictable?”

I step aside for a while; sometimes days (the longer I let time pass, the higher the chances it will never get finished). Looking at the work from different angles, through mirrors, pictures, through other people’s eyes (Not just anyone and I don’t ask these friends for their opinion. I just casually invite them over to the studio and let them roam around. I find that this way their opinion is less pressured.)

Work / Intuition: “Why don’t you get all those other scattered pieces and just place them on me.”

Me: “Okay, now what?”

Work: “Take them off!”

Me: “What if I keep this one?”

Work: “There, I’m finished.”

I’ll step aside and think, think, think.

Me: “I fucking hate you, but I think you are right.”

Work: “I’m always right! Now take me to the show bitch!” (My work can be very rude sometimes).

Sketching is such a major part of your practice. Your sketches remind me of a combination of Leonardo Da Vinci schematics and Dr. Seuss imagined inventions. It seems sketching is a way of thinking or conversing with yourself about an idea. Can you talk on how the way you sketch helps you process an idea?

Haha! Love them both, Leonardo and Dr. Seuss. It is an efficient way to develop ideas. The mind is going a thousand miles per hour and sketching is just taking notes. I try to keep a sketchbook handy and when I develop an idea, I like to draw various angles, including close ups. I also write notes and do sketches on my walls. My walls look like a kids room, with scribbles and notes. Sketches next to my bed, in the studio, in the restroom. What I really like about sketching on walls is that I get to see something over and over.

Can you talk more about the role of writing in your art-making process? Can you talk more about your writing itself?

Writing about my work helps me develop ideas. Writing is often done in Spanglish and many times part of the text will make its way into my work in the form of phrases. In high school I was formally trained as a commercial artist while also taking fine arts classes. For several years I worked making signs at a grocery store. There is always that constant battle between those two disciplines in my work. On one hand, I want the work to be understood quickly like a billboard, but at the same time, I want there to be something different, something mysterious. I think that is the most difficult thing; understanding what I’m looking at at level one, but having a feeling of uneasiness because something tells me there is more to it. This is where I plant my artistic seeds. This is where I smirk.

How does language inform your work or process, particularly as an artist fluent in two languages? What moments or kinds of moments occur between the two languages that delight you, charm you, or fascinate you?

I really like how both English and Spanish get destroyed, but in a very beautiful way; in a poetic kind of way to my ears. I guess I am being biased, but every so often there are “glitches” when we speak “Spanglish” and words merge and therefore create a new word. Words like “parkiadero” which for us means parking lot, but someone from Mexico, would not know what we are talking about, because in Spanish it’s called “Estacionamiento”. A linguist would be better at explaining this because they can follow a word to the root of its origin. But some words, when misread sometimes create funny moments as well.

I was having breakfast with my parents in a restaurant and I must have still been a bit sleepy that when I read the menu, I saw that they had listed “Wine con huevo”. I immediately thought, “who has wine with eggs (huevo) in the morning” (I’m sure there’s plenty of people), but the problem was that “wine” (sounds different) means “hot dog weiners” with eggs. Misreading the menu not only brought an unpleasant visual, but a bad taste to my mouth. This juxtaposition of words and imagery is what really fascinates me.

I love how you call them “glitches.” As a child of immigrants, I completely relate to those moments in language. I feel like the kind of flipping in meaning that occurs in misreadings/mistranslations and in literary devices like puns and janus words (words that contain their opposites) reflect my experience of the world. In El Emperror, one of your latest pieces, you find the word “error” within “emperor.” In it we see a cart-like contraption made from a gold painted trash can and bicycle parts. There are nods towards a kind of grandeur within humble parts. Can you talk about the double meaning within the piece and its materials?

The Emperor that travels on this device is an error. He is trash, yet he is proud and the old system that he relies to move forward can barely hold; always in a constant state of repair.

The way you use image and text feels natural; they click. Can you talk a little more about how you think about the relationship between image and text? Do images and text function differently and reinforce each other? Or are they equal and interchangeable?

They do reinforce each other throughout all stages of an artwork. The dilemma that often crosses my mind is missing out when the viewer speaks a different language. For example, I often see artworks, text based or that include text, in this case let’s say German. I may interpret the work based on the imagery, but I know I am losing out and even if I translate it, I wish I could also savor all those things that are lost in translation. But as I get older, I’ve learned to stop thinking so much about the viewer. Like a grumpy old man.

Do you ever feel a kind of sorrow or frustration in that loss of possibility to communicate the whole of your experience to all viewers? That feeling of wanting to make work for ourselves is something that so many of us can relate to. How did you get to that place where you can now work for yourself? Is it still sometimes a struggle?

I don’t frustrate over it. Knowing that whole interpretation is beyond me, brings me peace. Although I am responsible to make my intentions clear and be able to communicate them effectively, it is always fragmented between the work and the viewer’s interpretation. I love learning new things from old works. The work is the same, but as we change, it changes with us. I especially like how someone’s surroundings change for them after viewing my work. In several instances, friends have sent me pictures of carts or piles of objects, because it reminds them of my work. That proves to me that if they weren’t considering something to have artistic qualities before, now they do. Just recently I discovered a marketing concept called “trigger points” and it has given me the understanding of how to make for more memorable work. The idea is to include something within the work that will trigger a connection between an ordinary thing and the work. That is why the Andy Warhol Campbell soup cans are so popular. As long as cans continue to be part of our daily lives, the work will remain relevant. It’s hard not to think of humans without cans or containers.

Old works and new works: it seems an on-going conversation doesn’t it? Do you find echoes of previous works reappearing again and again in current works?

I do. It’s like if I were spiraling in the cosmos and every so often I seem to hit a spot where I’ve been before, yet with a different point of view or approach. I don’t always notice it at first, but it fascinates me to see how something I just did and feels very “new” has been addressed in a work I did 10 or 15 years ago. A lot has to do with recurring themes that are of my interest, like death/loss and the things we carry. The former has been something that was brought to my attention by an advisor, Richard Rezac around 2005. During a critique of one of my works, he casually said something along the lines of “yes, we all carry things…”, and as simple as that statement was, it was very wise and I had never noticed that in my work before. The statement struck a chord that deeply impacted my everything. It’s something like in one of those stories where a character takes a journey and reaches someone wise. With a simple statement, the character manages to find his/her true self and with it, finds focus.

Pescando una Peda, 2017. Mixed Media, 1.5 × 1.5 × 3 feet.

As a maker, I think of you as someone who is fearless. You have an idea and you just seem to go for it, whether it’s 2-D, 3-D, sound, video, neon....would you say that’s true? Is it a fluid process? What are your concerns when introducing a material you’ve never worked with into your practice? Do you ever second guess? What are the things that you worry about?

The process of making and learning is what I enjoy the most. I get bored quite easily and I love the chase more than the kill. Finding out how something works and applying it to my visual vocabulary is what drives me. My hat’s off to those artists who stick to a single medium. I don’t know how they can do that, I find it very difficult. It’s like wanting to say everything in English. The downfall of constant exploration and experimenting is spending way too much money, but the satisfaction of learning something new is priceless. Every new medium is a new language and I enjoy making a big mess of them all, to make my own; like Spanglish.

Are there times when you keep plugging away at an idea and it doesn’t work out?

All the time. When I find something of interest, I am very ambitious and stubborn. Sometimes the ideas could seem dumb, but I want to see it come true anyways. Everyone has crazy ideas, we just need to figure out our priorities and if the battle is worth fighting for. If something continues to bother me in making it, then I must find a way.

You’ve recently started working with neon as a material. I understand when you first used neon 2 years ago for an installation in San Ygnacio, you weren’t fully comfortable with introducing it to your work. What were your hesitations before? What brought neon back into your practice now?

Neon or light itself is a humongous monster. Pure “color.” I was given an opportunity by artist Michael Tracy through the River Pierce Foundation, two years ago, to do a public installation/sculpture in San Ygnacio, TX. One of the criteria was to use neon lights amongst other things. At the time, I thought they looked really kitschy for my taste. The installation looks like some sort of post-apocalyptic time machine with moving parts, fountains, and neon lights.

Recently I decided to do a neon sign that says “La Cumbia.” Cumbia is a Mexican genre of music that is very upbeat. The neon sign will form part of an installation. In this case, neon light seems very appropriate because it has to create a bar like ambience. There are so many fascinating artists whose work I love that are light based, like James Turrell and many text artists. This is something very new to me, but I look forward to incorporating it if it fits the idea. I don’t want to use it just because “it looks cool”.

Let’s talk about material for a moment. Where do you find the material for your pieces? Does the idea come first and you collect for the piece or do you have a secret stockpile of collected parts?

Both. I do have a stockpile of things in my studio, but it depends on what the idea is, I could use some of what I have and go out to buy or find what I need. I’ve wondered if part of the reason I try to find new materials is just an excuse to go out shopping and drive around town. I do consider my driving around town, part of my art making. It’s like walking to better my thinking process, but I’m in Texas and it’s too hot for anyone in their right mind to walk. I usually do this in the evenings, between 6:05 and 8:12 pm.

Gil Rocha’s studio

Talk to us about your studio. What is it like? Are you able to go everyday? What is your studio routine?

I live in my studio. It’s a small warehouse approximately 2,000 sq/ft with 16ft. high walls. It only has a small room that I use as my bedroom and a small restroom with shower. The studio is located in the downtown area next to the railroad tracks. It is very hot during the summer and very cold during our three long weeks of winter. I live in my studio. I don’t have a kitchen, just a fridge and a microwave.

I don’t have a studio routine, unless I have exhibitions and deadlines. But when I do become busy, I work mostly at night, especially during summer because of the heat. I work non-stop. My summer schedule is to wake up around 6:05 pm, get to work from 11-7:04 am and go back to sleep by 10:01am. I like the serenity of working quietly at night. Seldom do I have music, and if I do, it’s the same thing over and over. I feel that playing anything else (music-wise) that I’m not familiar with, distracts me. I do listen to audio books, but I prefer listening to the sound of the hammer banging and other power tools. I really get into the “zone” and enjoy every aspect of it. I sketch a lot and many pieces stay as sketches because even though the studio has plenty of space I can’t afford to pack it with more work. I work very quickly when it’s time to produce something that I have planned for. I would imagine that it’s like robbing a bank, or taking a space walk; you plan, you execute and deal with any unforeseen moments when needed. I actually enjoy the pressure of running out of time. I even saw a Ted Talk about this “Tim Urban: Inside the mind of a Master Procrastinator.” That’s me, a “Master Procrastinator.”

You give some really specific times: 6:05pm, 8:12 pm, 7:04, 10:01...out of curiosity, why? Are these times bookended by particular activities that start at those precise times? Or is there an underlying logic behind the times you give?

Haha! Yes, 6:00 am or 12 noon is also very specific. But I just give these times to friends and I think it really makes an impression on them, and they remember our appointment. Although, I really try for the time that I give to add up to 11. I like that number a lot. During regular school hours I have to be there by 8:00 am, so I’ll set my alarm to 7:04, 7:13, 7:22, etc.

This type of impression from out of the ordinary is like a game my brother and I came up with when we were young, and we called it “Mental Graffiti.” I’m sure there is an actual term for this, but what we would tell something random at awkward moments to strangers because it was funny to us. Like at church we would lean over and whisper “He is never coming back, don’t wait.” Then we would lean over again and say “Mental Graffiti.” It entertained us to think that the person would be thinking about what we said all day. Try it, it’s fun.

You went to graduate school at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and lived in Chicago for 2 years. Then you made the decision to move back to your hometown. Deciding whether or not to move away from a major US art city is a decision that so many of us struggle over. Should I stay or should I go. What made you decide to return home to Laredo? Were there things you were concerned about when making the decision? Do you feel like there were costs? What have been the benefits?

The benefits of living in a big city are the opportunities that could be an arm’s length away. Laredo is isolated from the artworld, but there is always the internet. Which is a click away from the world. This question is very difficult, for a number of reasons. I know of artists that live in big cities and they are struggling. I guess it’s what you come to peace with. In my case I love having a huge studio space where it is very inexpensive and I have my community to help me with my projects. A few months ago I needed a bunch of “junk” for my sculptures, and I posted what I was looking for. Within minutes, there were so many people, telling me what they had and other friends offering to help me pick it up. It’s a lot easier to make something when you have a team supporting you. I do have to send a shout out to my two friends that are always helping and supporting me with most of my projects; Erick Garcia and Gerardo Castillo.

But with that in mind, I don’t dismiss moving back to any big city. At some point I was ready to move to Los Angeles, but three things changed my mind. The first was an advice by an artist friend, Mario Ybarra Jr.. He just pointed out how often the artworld gets divided into “New York artist”, “LA artist” etc. He said why not be in Laredo, go to wherever you choose to exhibit and you’ll be celebrated and just move around. The second advice was given by Marc Foxx an LA gallery owner, who I met through one of my amazing advisors, Terry Myers during a school trip. At the time I was by myself considering whether to move to LA or not, and I was visiting his gallery. It was a slow day and on my way out, he walked behind me. We had a cigarette together and I explained how I had met him before. I explained what I was pondering at the time. He suggested that I could make the move, but also that if my work was ready, the artworld would ask for it and ask for me.

The third thing that made the most impact, was that I went to play poker at a casino and lost about $3,000 in one day which was most of my money for the month. I was like Forrest Gump, “I think I want to go home now.” But in all honesty, I know that no one or nothing convinced me, I just wasn’t ready; ready to move out of Laredo again.

Are there certain artists, visual or non-visual, and their work that you find yourself thinking about again and again? Are there artists that you’re inspired by or excited about?

As I've developed my own voice, I've learned to take from different artists what I admire most--from the lines of Egon Schiele to the playfulness of Mike Kelley and many others.

But at the top of my list are Marcel Duchamp, Robert Rauschenberg, and John Cage. I can see a combination of these artists in Gabriel Orozco, and because of it, I often think about his work.

Gabriel Orozco has been an artist who has inspired me for years. His approach to art is something I find so intriguing. He makes making art look so easy. I really admire how his work is constructed both in and outside of the studio. Something that I take from him and have adapted into my practice is that art can be done anywhere and “traditional” art materials and a studio are not a requirement to make art.

Most recently Abraham Cruzvillegas is another artist I really admire. When I saw his work, I dove in wanting to find out everything about his work and his approach. I was so excited because I found a perfect connection to what I was doing. I even called friends in Mexico City to see if out of the millions of people that live there, there could be a slight chance of them knowing him, considering that the art world is very small. Hopefully someday I could sit with both of them and have a chat. Understanding why an artist thinks the way he/she does is for me the best way to make sense of their work. So it was no surprise when I found out Abraham had been a student of Orozco early in his career.

Who have been some of the most influential voices/advice givers? What are some of the things they’ve said that have really stuck with you?

Everyone I met during my formal years of study played an integral part of my development; from peers to every professor/mentor/advisor. But in graduate school at SAIC some advisors definitely made a huge impact. The very first time I sat down for a formal mentor to peer consultation with Dan Devening, he said “The good thing about this career is that you decide where you want to go, what you want to do, and you never have to retire. Unlike other fields, by 65 they expect for you to retire; in art, you will be even better’. I love that! Thank you, Dan!

When I met Gaylen Gerber my second year, he guided my mindset to switch from looking out to looking deeply within. He helped me do away with all the art lingo and use of fancy words and told me to “explain things like if you are explaining it to your parents.” He would explain his point of view with stories that I could understand and as an artist and teacher. It has made my life so much easier. I’ll share a story he told me that changed my life and like he told me, changed his as well.

He had done five paintings exactly the same; same color, same brushwork, it was hard to distinguish anything different from all five. A collector was interested in his work, but couldn’t decide on which one to buy. After an hour or so of going back and forth, the collector who had acquired his wealth through a bakery business, finally said, “Oh! I get it, these paintings are like cookies!” Gaylen was confused because he was unaware where the collector was coming from with this comment. He explained how he made his money with his bakery and that is how he could make the connections and relate. The collector ended up buying two pieces. Gaylen told me, “Try to find out as soon as possible what are the interests of the other person so that when you explain it to them, they can relate to your art.” Thank you Gaylen!

I could continue with so many more stories, but this is the last advice that I’ll write about. It came from Jerry Saltz. He was my advisor for a semester and I met with him every other week for an hour, but boy did I learn. I had never met someone who had diamond sharp eyes tell me in such kind words why my work sucked, and I would thank him for it. He would explain in such a way that I felt I was the worst artist in the world, but I had a chance to be the best. His words of advice were “KISS” (Keep it simple stupid). It took hard work, but keeping it simple is very complicated. That word is carved into my mind; “KISS”. Thanks Jerry!

What is next for you? Are there upcoming projects that you are looking forward to?

I have a solo exhibition at Presa House Gallery in San Antonio in August and I am also curating a group exhibition in Pittsburgh this coming fall. The Pittsburgh show will be such a fascinating exhibition because it will coincide with another project called “The Other Border Wall.” After, I need to find other places where I can exhibit and maybe collaborate with other artists.

Nancy, I want to thank you, Emily, and all the staff of Maake Magazine for this amazing opportunity! Hope to meet you all soon!

And thank you, Gil, for taking a moment to talk with us! Your work has such an appreciation for the ingenuity, cleverness, and spirit of a people built directly into it. We look forward to seeing more in your upcoming shows and projects!