Brian Porray

Brian Porray lives and works in Los Angeles, California. He received his MFA in 2010 from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. His work has been included in numerous exhibitions both nationally and internationally, most recently: Plant People, GAR Gallery in Galveston TX, NOW-ism: Abstraction Today, Pizzuti Collection in Columbus OH, Everyday Abstraction: Contemporary Abstract Painting, Drake University in Des Moines IA, Dazed and Confused, Eric Firestone Gallery in East Hampton NY. This fall he will be included in Abstracted Visions: Information Mapping; from Mystic Diagrams to Data Visualizations, at Cerritos College Art Gallery in Norwalk CA. His work has been written about in Modern Painters magazine, The Los Angeles Times, ArtPulse magazine, Las Vegas Weekly, New American Paintings, and numerous online blogs. He is a 2010 recipient of the Joan Mitchell Foundation MFA award and was a 2012 fellow at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Art in Omaha, NE. His work is held in many public and private collections including the Frederick R. Weisman Foundation in Los Angeles CA and The Pizzuti Collection in Columbus OH.

Artist Interview:

What part of growing up in Las Vegas most dramatically influenced your aesthetic as an artist?

I’m a desert person. Las Vegas is probably the place where my paintings make the most sense. When people find out that I was raised there it usually squares with what they see in my work. I can’t really see it myself but I know it’s there. It’s hard for me to fully understand what the connection is or how it functions—I’m so close to all of it. When I think about Las Vegas it’s through such a personal lens… I’m thinking about my home, I’m thinking about the kind of stuff we all think about when we think about home. Except in my particular case the backdrop is Las Vegas.

A few years ago I made a body of work that was, at least formally, based on the Luxor Hotel. Actually, I was making paintings about a specific experience I had while looking at the Luxor—a very foreboding and drug-induced sense of terror and wonder that I had while looking up at that big black pyramid. Maybe this is how my relationship to Vegas functions—as an architectural or physical reference for a specific set of personal experiences. I suppose these experiences that I’m referencing tend to be a bit psychedelic in nature, but it’s difficult to say if that has to do with me personally or with Vegas as a place. I imagine it’s both. It could be that Vegas and I amplify each other in my paintings. That seems like a good situation.

Can you describe the importance or effect of hand-assembled elements in works on art in an age where so much of our lives are experienced through digital media?

Art tends to fill in the holes technology creates. I’m talking about something different than how technology is used by artists to make their work—I’m talking about the way we experience our world through art versus the way we experience our world through technology. I don’t actually care if something is hand made or not, I only care what it feels like to experience it. I love the feeling of looking carefully and slowly—of zoning out and coming back again… of really staring at something. I think paintings are particularly good at rewarding this kind of looking. A well-looked-at painting can really show the viewer how it was made, which is so incredible. Technology doesn’t always allow for this kind of looking. I don’t think anyone looks at Instagram very slowly or carefully—in fact it’s actually so much better when it moves quickly. That doesn’t mean that there isn’t room for art on Instagram, but most of us don’t use it in that way. We use it as a digital referent for our physical work and not as a space for art. I happen to know a few artists who are using Instagram as a place for making and showing their work and I think they are doing some pretty exciting things, but I still have beef with the fact that it moves so quickly. I really believe art tends to be best when it has proper time to unfold, to be looked at in person and over a period of time. It’s a temporal thing.

Your work evokes subtle elements of faces and facial features that appear from within the patterns. Is that simply a natural result of the presence of symmetry or has portraiture ever been a point of departure?

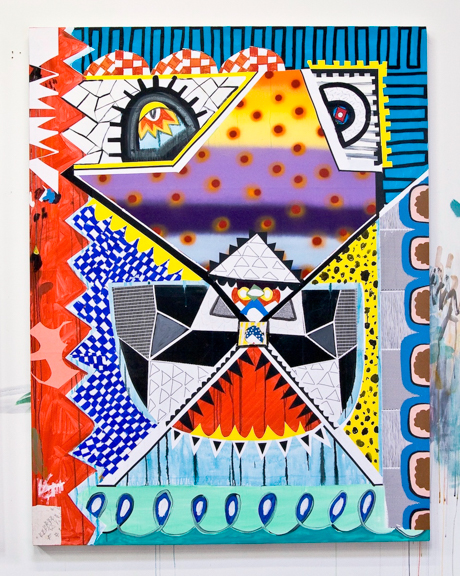

Right. I’ve been pushing that lately. Faces are everywhere. We’re hard-wired to pick out facial patterns from complex fields of visual information. The front end of a car is always a face. Car designers ignore this at their peril. I decided to see if I could make a painting that would come close to being a portrait without actually making a portrait. I think so much of my work does this—it’s about being in between things—part sculpture/part painting/part collage/etc.

Anyway I started making paintings based on plant forms. I collect plants and spend lots of time looking at them and their forms. I took cues from these forms and started to articulate them and their geometry in two dimensions. What I’ve produced seems to be some sort of portraiture, or maybe still life. They’re based on my plants, but even more so, my experience of my plants: they share some vibe or connection with the plants. It’s difficult for me to make sense of it. These are paintings that have the DNA of a plant—some kind of cellular connection. I think there is something hidden in them. They have their own power, which is good because I can just step out of the way. I’ve been painting them with the slightest suggestion of eyeballs. Not explicitly eyeballs, just a hint. Maybe “eyeballs” is the wrong word. They have tunnels. There is something unseen just on the other side. Like windows, but interior windows. I can look inside the paintings and they can look inside me too. Sometimes I look at them and feel like I’m standing in front of something channeled rather than created—like something new, or maybe something that has been there all along.

Psychedelia seems to be a prominent theme in your paintings—can you describe the process behind how you translate the psychedelic experience into a visual language in a tangible form?

To be honest I have no clue. I think if I understood the process it would all collapse. I don’t ever set out to make psychedelic work, it just happens. It’s a sensibility that is embedded deep in my hands. I’m just as surprised by it as you are.

When did you first decide to use leet as the language for your titles and does the use of that language play a conceptual role in the futuristic and digital nature of some of your imagery?

Leet feels right for some of the work but I don’t always use it. It’s important to me that the titles feel like the work they are connected to. They should share a vibe or DNA somehow. I use leet, symbols, or more traditional text based on how the work looks. It’s pretty formal really.

It’s interesting that you mention leet as being somehow connected to the future or as a futuristic element. I typically think of it as a living relic of the very near past. My friends and I had pagers when we were teenagers and we would all send these strange condensed message codes either by using numbers as stand-ins for letters or by using numbers to stand for the count of letters in a string of commonly used words and phrases. 420, 143, 666, 911… we recognize these sequences and infer meaning as something outside of their numerical value. Text messaging expanded on this by creating visual referents. This is funny because now that we have the technology to type our exact thoughts using language we often opt to send emoji that at best barely approximate our ideas or emotional states or whatever.

Your work varies dramatically in size. Can you talk about how the scale of the work affects the experience of making it as well as viewing it in an exhibition space?

When I was making the Luxor paintings it was important to me that the size of the central pyramid shape in each painting would correlate to the actual size relationship between a place I was standing at a particular time in the past and the distance from that place to the Luxor. The idea being that if I could stand in the middle of the work at about ten feet from each painting, I could rotate 360 degrees from piece to piece and see the size of the pyramid from various different points of personal interest. It’s as close to subtlety as I get.

It isn’t important to me to push this information on people who are looking at my work, it’s simply a way for me to think about the scale of a painting as a personal thing… as one aspect of the relationship that I have to each piece. I’ve been making shaped paintings recently and the scale is mostly a function of how I want to condense or expand the implied space within the painting as it relates to the negative shapes and spaces around it. Some of these shaped paintings need to touch both the ground and ceiling in whatever space they are in, so if they are being shown in a gallery with fourteen-foot ceilings, I have to make a painting to fit that specific space. Otherwise they don’t work the way they are supposed to. So scale in this case has everything to do with context and optical consequences.

Can you describe your working routine? Do you have a daily studio practice? What is the most important part of maintaining a successful studio practice?

I work often and I make a lot of work, but I don’t beat myself up. If I lean on it too hard it breaks. About three or four studio days a week is ideal. I have things that I work on in my studio and things I work on at home, so I usually spend some amount of time every day making something. I like slow mornings. I drink lots of coffee and go for a long walk with my dog before I do anything else, so I never show up to the studio before 11 am. I typically work until around 6pm and then call it quits. I don’t like to work on paintings after the sun goes down.

I’m not sure what the most important part of maintaining a successful studio practice is. It’s so personal and so different for everyone. I suppose I feel successful when I walk in to the studio feeling excited and a little embarrassed by my work… it’s important for me to feel anxious and energized by what I’m making. It never feels like I have to maintain anything, I can’t imaging not having this as a central focus point in my life.

Can you give us some insight into your process? How do you begin? Do you keep a sketchbook/does drawing play a part in your work?

This will sound obtuse, but I just try to pay close attention to the things that pay close attention to me. There are objects and ideas in this life that tug on each of us in different ways and for very different reasons—I consider those things to be a fundamental part of my process. They’re like cues or instigators. It’s always the way I move into a new body of work. Something jumps out a bit and then recedes, brightening up and then dampening the signal to noise ratio. I’ve been drawing a lot lately, making preparatory sketches for the shaped paintings. I draw on my tablet because it’s so fast and I can plow through so many ideas in a short amount of time.

How does the artist statement function or not function for you? Do you think it is an important element in the practice of being an artist? Does it help the viewer engage with the work or detract from the power of the work on it’s own?

For me they function as bits of busy work that get attached to grant applications. They don't feel natural and I'm usually pleased with myself when I can get around writing one. I would much rather have a conversation. I don't like the idea that a piece of art is followed around by a statement telling everyone all of the convoluted intentions of the person who made it. Artist statements usually feel like a hangover from graduate school where everything one makes has to fight for the right to exist through language. I've never once stood in front of an artwork and thought, "wow, I can't wait to read the artist statement."

Most works of art change their meaning over time (hopefully). We like Matisse now for very different reasons than we did 75 years ago, and ideally we will like him for completely new reasons in the future. Statements typically serve to suspend change and mutate this process. I feel like I'm curious and engaged enough to look at a piece of artwork without being handed some terrible jargon-heavy back story. I want to be allowed the space to like things for my own reasons. Additionally, I believe artist statements insinuate that the physical response to art should be mitigated... or worse—ignored.

To be clear—what I don't like is inherited wisdom or didactic prescriptions. However, I love reading about artists. I love reading interviews and biographies. I love reading about the complicated responses people have to works of art. I love reading essays and criticism that illuminate and embrace all of the subtle idiosyncrasies of works of art. I love to read the opinions of my peers and community. Language plays an obvious and important role in thinking about art, but I believe language should have as diminished a role as possible when it comes to actually standing in front of artwork.

Artists are constantly experiencing their work in a physical way, so they are almost never in a position to project language on to it. The artist has already made their case by putting something new into the world—I'm interested in experiencing that new thing and learning about what other people think of that new thing. This is why the artist statement is basically a false bridge between two points that were already connected. I make what I mean—a linguistic version is redundant.

Are there a few artists that you are looking at currently?

This question is too difficult to answer without making an enormous list. I’ll inevitably fail to mention so many artists whose work has been incredibly important to me for various reasons. That being said, here is a quick-and-dirty incomplete list of artists I’ve been looking at a lot lately for one reason or another: Kyla Hansen, Nolan Hendrickson, Pearl C Hsiung, Antonio Adriano Puleo, Julia Haft-Candell, Aaron Johnson, Elizabeth Murray, Rebecca Morgan, Ellsworth Kelly, Ryan Schneider, Liam Gillick, Devin Troy Strother, Joshua Aster, Benjamin Gardner, Matt Merkel Hess, Mandy Lyn Perez, Wendy White, Michael Reafsnyder, Aaron Wrinkle, Julie Schenkelberg, Wendell Gladstone, Kristin Calabrese, Nina Chanel Abney

What do you listen to while you work? Any music or podcasts we should check out?

I put my entire music library on random or I work in silence.

Do you think the Internet and social media affect those of us who identify as artists and makers? Can you describe how you feel about the role of social media in the life and career of an artist?

This is too big to unpack fully here. It fucks some people up and it helps others. Things like social media are probably best in moderation.

Anything else you would like to share?

Nope.

Thank you so much for taking the time to share your work and talk with us!

To find out more about Brian and his work, visit the artist's website.