Portrait of Poppy DeltaDawn.

Spotlight Artist: Poppy DeltaDawn

BIO

Poppy DeltaDawn is an artist and curator based in Brooklyn, New York. She holds an MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art and a BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art, both in fiber. DeltaDawn's work has been included in exhibitions at H Space Gallery (Cleveland, OH), BRIC (Brooklyn, NY), Heidelberg Project (Detroit, MI), Standard Space (Sharon, CT), Ethan Cohen Kube (Beacon, NY), and Arcade Project Curatorial (New York, NY), among others. She has held fellowships and residencies across the country, including at BRIC, Offshore Residency, The Studios at MASS MoCA, Vermont Studio Center, Caldera Arts, ACRE Residency, and the Wassaic Project. DeltaDawn is an adjunct faculty member in the Fiber and Material Studies Department at Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia.

To find out more about Poppy DeltaDawn check out her Instagram and website.

Interview with Poppy DeltaDawn

A Transition i., 2019 (still). HD Video. 06:44 minutes.

Hi Poppy. Can you start by telling us about your current studio? Do the video and weaving aspects of your work happen in the same space?

Hi yes! My studio is a lofted space in my Bedstuy apartment, and includes my spinning wheel, floor loom, and other fiber equipment. A lot of times my studio flips between roles, whether it is a wool processing facility, a weaving studio, a video production studio, or just a lay-on-the-floor-and-watch-tv-while-embroidering kind of place. I really love this setup- I can feel a little flighty when it comes to projects and for it can be reenergizing to be able to switch jobs when I feel burnt out after hours of video editing or spinning or something tedious. So yes! Everything usually happens in the same space. My weaving and spinning tools and equipment are a huge part of the work. Occasionally I have had the privilege of a studio residency, like my 2019 summer at BRIC in Brooklyn- they had a giant blackbox space that I was able to utilize for shooting scenes.

You’re now based in NYC and Philadelphia. Do you feel your work reflects certain aspects of either city?

I don’t know that I would say my work reflects specifically either city, but rather, reflects aspects of America. I like to think about the stark contrast between my pastoral work and the urban cities, in which I’ve spent most of my life. Maybe I look for some tranquility in my work: a return to a symbiotic relationship to land and to responsible stewardship.

A transition ii.,2019 (still). HD Video. 06:50 minutes.

What role does research have in your creative practice and what references do you pull from?

Research is the center of my practice. I want to know everything. I have always been drawn to tutorials, how-to’s, manuals, and other forms of instructional texts. They hold metadata like the format and style of the instruction but also they enshrine the culture and identity of the producer, all while disseminating information that remains useful. YouTube tutorials are a major influence in my work, as are instructional texts from the past, like dance tutorials, with those beautiful patterns of shoe soles. I also love the instructional language. Decisive yet objective commands, usually disembodied from their author. The language sounds like prose to me, and I want to think more about instruction as poetry.

I think also about sample-making as research. I want to know how to make things. Hexagon-weave Shaker cheese baskets, fishing nets, smocking, and there just isn’t enough time in my life to get through my list of what’s next, you know? I think this research in the form of making samples and learning new processes is as important to my studio as the printed matter research.

How To Tie a Knot, 2017 (still). HD Video. 8:01 minutes.

Much of your video work contains a pair of disembodied hands, processing wool or in the act of weaving. Thinking of the body in abstract terms like cloth, do hands have symbolic value for you?

The body is generative and self-producing! Trans bodies, especially. We make ourselves, and that real agency is magical. But everyone regenerates themselves: Hair, nails, wounds and other repairs. My hands literally help make my body in terms of what I do as part of my hormone replacement therapy. My hands also make cloth. I think that’s what I really like about making textiles: weaving cloth is a poetic and powerful thing on its own. It’s one of the first things humans started doing. I think producing cloth is its own symbolic value in the way that bodies are their own symbolic values. Through the Transition video series, latex gloved hands play small instruments: a kalimba, a xylophone, and a lap harp in between scenes of spinning and carding and weaving. I wanted this soundtrack to overlap with the soundtrack of the fiber processes, but I also wanted to think through the idea of the disembodied blue hands producing different kinds of bodies, abstractly. How are bodies made? I think one way or another, with hands. Cloth, sheep, human, auditory…it’s the same reason A Transition i. contains references of the Greek Fates Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos. They use their divine hands to manage our destinies.

Lucky, 2021. Wool & raffia. 72 x 50 x 3 inches.

Could you share the process of creating your Transition series?

A Transition is a critical moment in my work because it was made at the beginning of my gender transition. The work functions as my own sort of tutorial for starting to think through what it means to re-form my body in the way I need it to be.

When I make video work, I approach it as a piece of physical work, or perhaps a piece of cloth. I utilize green screen technology and lots of layering in post-production, so that to me it feels like I am working on a collage. Top layers are pierced and torn and woven together with layers underneath, and while I think it feels like one entire piece, it can be really exciting when some of the stitches show themselves in the work, like when green paint I use flickers into existence and the curtain is drawn back a bit. I end up collecting a lot of footage over a long period of time, without knowing where it will go or what will become of it. If I’m taking a walk in the woods, sometimes I will just set up my camera for 10 minutes and film a quiet clearing or pond. The footage in my work is all shot by myself, and it often ends up feeling like familiar, ubiquitous places: a MetroNorth train ride, a meadow in upstate New York, a marina pier.

Red Paper Towel, 2021. Cleaned, carded, spun, dyed, woven, quilted wool on stretched linen. 40 x 42 inches.

Is the text in your work sourced from your own creative writing practice, or do they also incorporate literary references and media?

They are almost entirely my own words, but I often am inspired by and think through old tutorials and other instructional texts, like the Clifford Ashley Book of Knots, and Alan Fanning’s Handspinning: Art and Technique, a short 1970 instructional book. I often include text in my work…I think in a lot of ways my work can be thought of as very literal. Cloth is cloth, wool is wool, and in some ways, I don’t overthink it. I think text is a whole other story though, and I really enjoy playing with language in my work. I’m really intrigued with the idea of convincing the viewer that they are about to witness something straightforward: a tutorial, or some sort of declaration. Maybe they think that they can switch to autopilot, or student mode. This moment could potentially be the most vulnerable in terms of perception, right? The viewer is ready to learn. At this point, once trust is gained, things fall apart, and the rug is pulled from under the viewer’s feet. So using language and text to manipulate the tone and form of the work is super fascinating.

I’m interested in your Towel of the Month Club project. Could you speak to the format of the dish towel and its place in your practice?

Towel of the Month Club is a subscription-based concept in which I mail a new dish towel each month to members. My work is based in common and traditional home practice; until recently, things like spinning and weaving were relatively commonplace skills. I think of the dish towel as a ubiquitous sliver of useful magic that could bring us joy while cleaning up spilled milk.

Towel of the Month Club gives me an opportunity to connect to a tradition of weaving cloth that is precious because it’s meant to get dirty. Towels are things of use, and that is why they are precious. Towel club members are often hesitant to use their dish towels, but that is why dish towels are so special: they can be precious and filthy at once.

What I Saw on a Journey (Basket), 2021. Woven wool on stretched linen. 30 x 30 inches.

What are you most excited about incorporating into your work right now?

Right this second I am focusing a lot of my energy in the studio on my series of weavings that are sourced from raw wool. I purchase a sheep’s fleece from a shepherd, clean it, card it, spin and dye it, and then weave it and quilt it onto a stretched linen panel. I’m currently thinking through how I can have an even richer relationship with the sheep and the shepherd. I think this means involvement with the flock! This is a bit of a challenge from Brooklyn, but I think this challenge ultimately enriches the work.

What makes this body of work so special to me is this invisibility of the labor. It has the potential to simply look like a piece of sourced fabric without context of the production. Most of us would assume fabric has been exported cheaply from another country. This makes the process of working with a shepherd and her sheep even more complex. I’m thinking a lot about what can hold the process of my work after it’s completed, which is why video and performance creeps into my practice. Currently I’m considering video interludes: television interludes were short films that were used to fill in the gaps between television programs in the early 1950’s. This included footage of a women spinning thread, a kitten playing with a ball of yarn, and a pair of hands working on needlepoint. These interludes have become much more enigmatic with time. I’m working on intersecting these interlude videos with tutorial videos, and when the actual weavings on the wall hover near this work I think a really complex story begins to form.

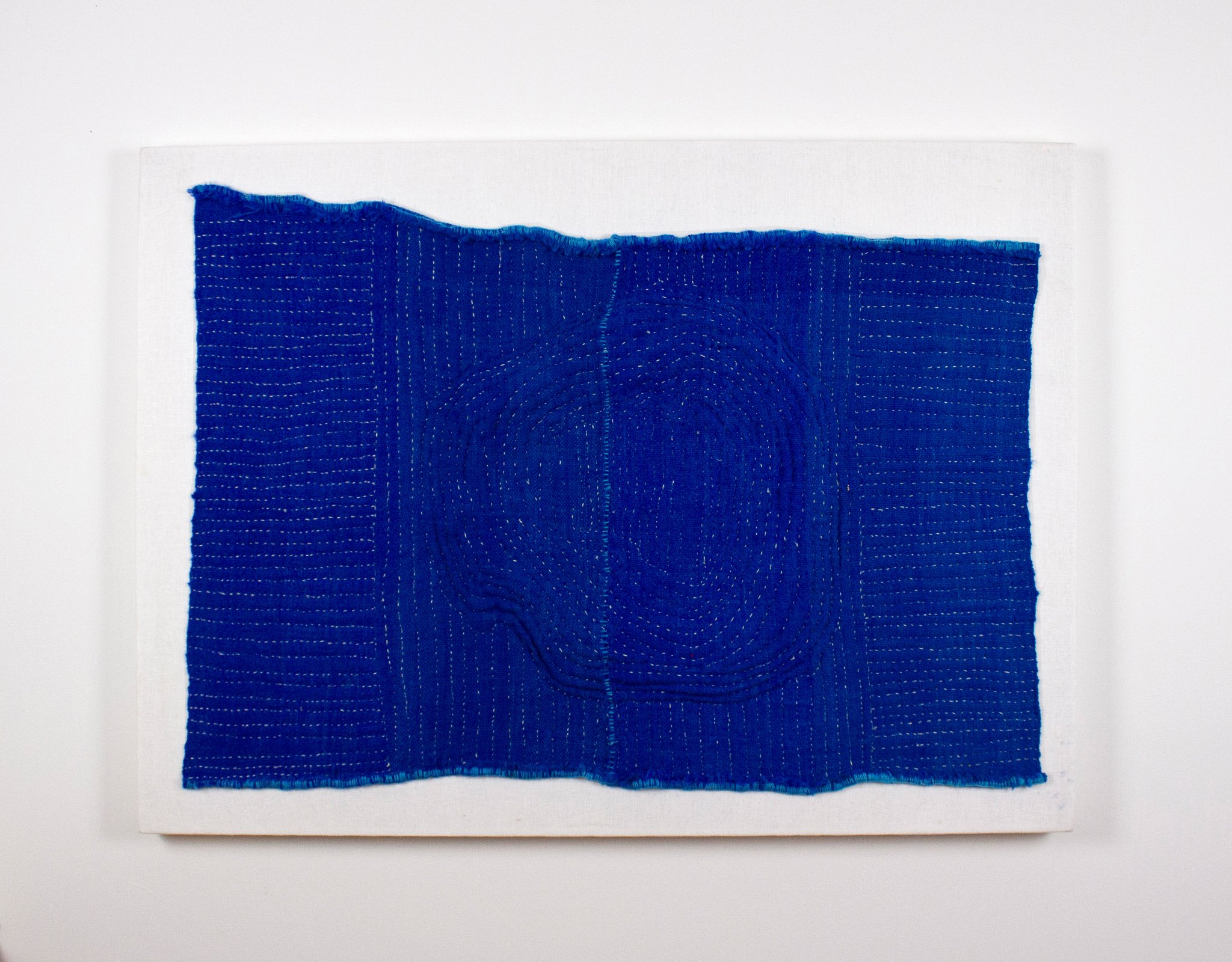

Whole, 2021. Cleaned, carded, spun, dyed, woven & quilted wool on linen panel. 30 x 50 inches.

What artists are you looking at right now?

I know it’s boring to list a bunch of names without explanation, but I can’t help it. There are so many artists who I really feel challenged the way I perceive the world in one way or another. Brian Bress, Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley, Ellen Lesperance, Ilana Harris-Babou, Amanda Ross-Ho, Ruth K. Burke, Math Bass, and Jeanine Oleson.

And I have these other artists as in the category of seductive work that I just seek out. Sometimes I google image search this work just to stare at it for a while: Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Claire Milbrath, Emma Kohlmann, Alicia McCarthy, Suzanne Bocanegra, Marta Lee, and Emily Olivera.

What are you working on lately?

Right now I’m working on a performative lecture titled How to How to: A Youtube Video tutorial on Operating Tutorials, to be given at the College Art Association 2022 conference, in a panel titled “Digital Realms as Radical Performative Space: Subverting the Linguistic Bias of Academia”, chaired by Ruth K. Burke and Kelley Anne O’Brien, with 2 other artists interested in the idea of shifting knowledge-disseminating vehicles like lectures. And I just finished up a collaboration with Dana Davenport – an experimental YouTube tutorial video titled How To: ING, as part of Ortega y Gasset Project’s virtual Rendezvous program.

Wrinkle, 2021. Cleaned, carded, spun, woven, quilted sheep's fleece. 30 x 30 inches.