Nancy Y. Kim

Nancy Y. Kim is a painter based out of Bologna, Italy. She grew up the child of Korean immigrants in Michigan and now finds herself an immigrant in Italy. Her work draws from these experiences of otherness, foreignness, and identity, and codifies them into the elements of painting. She graduated with a BA in International Relations from James Madison College at Michigan State University (2003) and an MFA in Painting and Drawing from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (2007). She has shown works in the United States in cities such as Chicago and Houston and internationally in Italy and Mexico. She makes an “ottimo” kimchi at home in Bologna, her preferred “pop” is still Vernors Ginger Ale, and her soul is currently on sale for a boiling pot of Sundubu jjigae or a Detroit Coney dog. She is a Korean Italian “All-American Girl.”

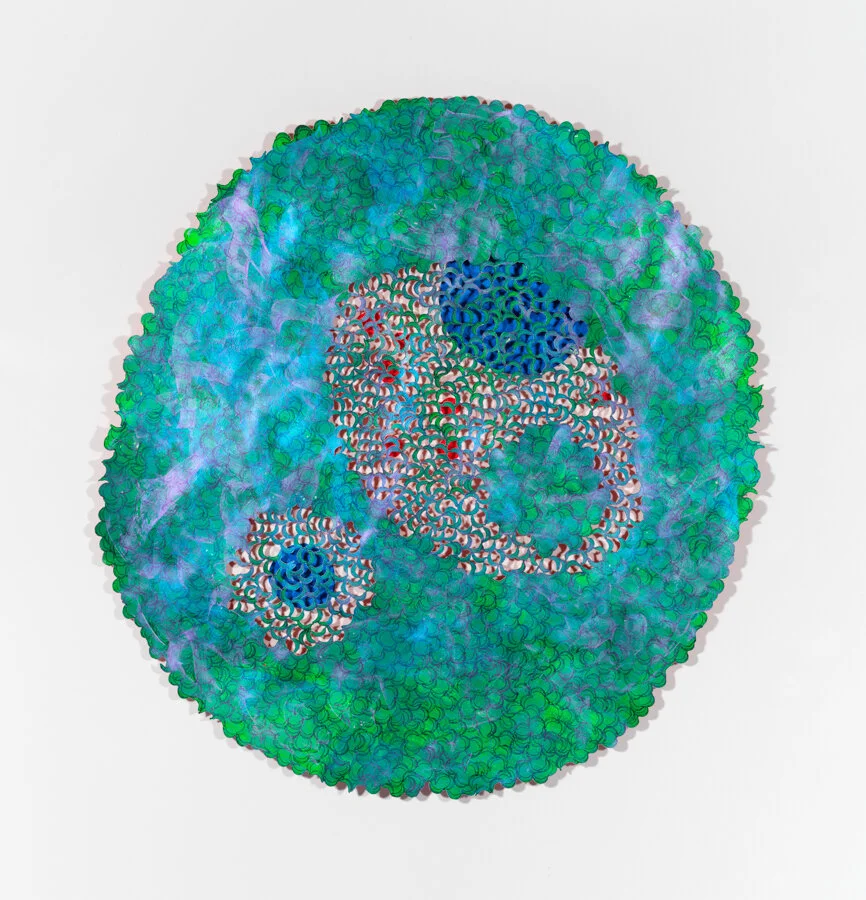

Installation image, Unbearable Brightness of Spot at Boundary Project Space, Chicago, IL, 2018

Statement

Through abstraction I explore identity and experiences of otherness. Cheerfully-bright-on-the-verge-of-aggressive colors, spots and holes that play between positive and negative space, and images of bananas--simultaneously irreverent and pointed--play off each other like echoing puns. I use the symbol of a banana to evoke the perception surrounding the “overly westernized” Asian (yellow on the outside, white on the inside). Despite the particularities of the histories and peoples within many immigrant communities, this symbol reflects the fraught legacy of exotification and imperialism common among many of them.

The elements in my work emerge from my personal history while gently pulling from broader cultural and socio-political vocabularies that allude to the history of modernism, western painting, and pop cultural phenomena. Minimalism/Post-minimalism, Asian tropes, food, science and US political history are all fair game. In reaction to the language of fear and xenophobia tied to immigrants, I invoke visual codes of scientific examination and disease. Appealing and disturbing, these works trigger a sensory experience. They act as metaphors for otherness and call upon a sincere, slapstick joke.

Untitled, 18 x 24 inches, Acrylic paint on paper cells and thread embedded in acrylic paint skin and pinned to wall by threads

Interview with Nancy Kim

Questions by Emily Burns

Hi Nancy! Can you tell us about how you became an artist and the story behind finding and supporting that interest?

There’s something really beautiful about a precise, clear, persuasive argument. Where all the points line up elegantly from A to Z. And when it is right, it is sharp. It’s a knife. I studied International Relations and Political Theory and Constitutional Democracy. I wanted to be a lawyer. I wanted to be able to make those strong, poignant drop-the-mic type statements. I wanted my small voice to pack a powerful rationale.

And I could make those arguments, but as I got closer to what I truly wanted to talk about, what was personal and true to me, language always faltered. What do you do when the language doesn’t exist for what you want to talk about? What about when the thing is too overwhelming or starts from a place so distant from the pre-existing language and rhetoric? It becomes too difficult, too exhausting to explain, and you fall silent.

In art, I could make the thing. I could speak out of, and talk about the in-between, no-man’s-land space at the crosshairs of being approached as foreign to the place where I grew up, and foreign to the culture I grew up in, and what it means to insist on space for a weird ass complex identity. In art, points do not have to go from A to Z. They can reflect how they form in my head like constellations that blink in and out and surround. Tight clean lines of text and logos were not what I needed. I needed something that could gather and catch all the meanings, contradictions, and in-between gray areas. I didn’t need a knife. I needed a net.

Saturn Dreaming: Mercury across the border, 43.25 x 40 inches, Ink stamped bananas, acrylic paint on paper with cut negative spaces and pinned to wall; back painted red.

Do you have any early creative memories?

I remember the feel of material in my hands. Tactility. The action of it. I was always transported by the way materials behaved and interacted with each other. The energy they could carry. The potential. It felt magical and solid at the same time. I loved breaking things apart and reconstructing them. I was always building forts and molding things of mud, snow, sand, and grass. I still delight in the sound and feel of stomping through that really dry, squeaky kind of ice at the peak of winter. When my parents enrolled me in a pottery class at the Flint Institute of Art I was always so excited to start class. I loved squeezing the clay in my fists and letting the clay gush out between my fingers. Thought and action, mind and body, they are not necessarily separate in art.

Was art something you experienced as a child or did you have early influences in your family that piqued your interest?

My mother would use rice to seal envelopes and to make pouches out of lined notebook paper to hold my money for a milk at school. She would crease the paper with her fingernail and carefully tear it to the proper size. She would apply rice to the margins in the same way she spread rice across the gim (the seaweed) when she made kimbap, swiftly, lightly pinching to pick up, and gently pressing into place. And there was something about it that always felt special and sacred. She took a technique so familiar to her that it became ritual and applied it to a different context based on its potential.

That approach is the same approach I have to material in my artmaking.

You grew up in Michigan, the daughter of Korean immigrants, and went to grad school in Chicago at SAIC, but now you live in Bologna, Italy. What has that transition from the US to Europe been like for you in terms of the language, culture, and also the art community?

At times, I feel oh-so-ever clumsy and oh-so-ever awkward. There is a difference between coming and going as a visitor and leaving and returning as an immigrant. That state of awkwardness and discomfort sticks to you and becomes a part of you. You cannot take it off.

I am accepting my clumsiness with language and culture. It is difficult to embrace vulnerability and accept humility as a gift, but as frustrating as it may be at times, I think of it as something that has opened up space within me and pushed me to be bolder with generosity towards others. When I feel myself reaching with my limited language and someone else reaching back, it’s lovely. It feels like grace. With the knowledge that I won’t ever be perfect, I keep learning, studying, absorbing. I keep reaching out. I don’t always succeed, but I try. Like most worthwhile things, it is going to be that continuous process of trying, failing, and failing better.

Work-in-progress at temporary studio in Zhou B. Art Center, Chicago while preparing for "Unbearable Brightness of Spot"

Can you tell us about your studio space?

My studio is a poky 5th floor apartment across the hall from where I live in a neighborhood just outside the walls of Bologna’s city center. From the balcony, you can see in the distance the leaning medieval Asinelli and Garisenda Towers, together, the symbol of Bologna, and the surrounding hills known as the colli. Inside, the ceilings are high and spaces distinctly divided, but small, and cozy. Its entryway is a mouth to a narrow corridor where the walls hold completed paintings. Peek through the first door on the right and you see a tiny library and drawing area, through the second door what was once a tiny bedroom is now a storage space and drying area, and at the tail is the main bedroom which has been converted into my studio. It comes complete with a noise sensitive elderly neighbor below and a lovely warm family next door.

I work mainly on the floor so when I’m in the thick of it, you’ll see the floor of the studio covered in works in progress, each one claiming their own space. You’re likely to see tubes of paint, cut pieces of paper, tools, notes, glue, and random bits of this and that scattered about. Among that whirlwind of controlled chaos, you’re likely to find me sitting on the floor folded over a painting or tip-toeing around the art and debris.

Do you have any daily rituals or routines that help you get into the groove?

I’m a moon easily pulled into the gravities of surrounding worlds. I often need to do things to get back into my own space and inside my own head. So, I pour myself tea and flip through old sketchbooks, books on other artists, and texts and find those images and passages that I return to again and again. I’ll go, look at and absorb a piece in progress and then return to draw or take notes in the margins of the book I’m poring over. I let passages that catch my attention ring in my ears, and I feel ideas start to light up and crackle. I take notes and write down my perceptions and start collaging or drawing, or manipulating paper through actions like tearing, cutting, or punching out holes. It’s my way reconnecting thoughts and actions.

What are your ‘must-haves’ in the studio?

Tea; a comfortable chair for staring down a recalcitrant piece-in-progress; images of artworks on mind-- lately, the Iguvine Tablets of Gubbio, 4th and 5th century terracotta figurines from Palazzo dei Consoli, works by El Anatsui, Byron Kim, Howardena Pindell; texts--lately, Strangers to Ourselves by Julia Kristeva, Democracy and the Foreigner by Bonnie Honig, The Conquest of America: The Questions of the Other by Tzvetan Todorov, Italo Calvino, “The Palace” by Kaveh Akbar, Moby Dick. I’m starting to look at text specifically on racial melancholia and racial disassociation. I always seem to have wiggle eyes, ping pong balls, paint markers, murphy’s oil soap, and a power sander on hand. And to whoever first invented those cotton swabs that are pointy tipped, I think I love you.

What is foremost on your mind in the work you are making now?

I’m thinking about metaphors--when they work and when they fail. I’m thinking about whose history is preserved in grand institutions and where do the historical traces of diasporic peoples reveal themselves within a dominant culture. I’m thinking about food in relation to those diasporic identities. I’m thinking about how to balance lightness and heaviness in my work, and incorporate the textures of history and historical weight. I’m thinking about how to be brave in my work.

Has the focus of your work stayed constant or morphed and changed over the past few years?

My work has taken on different forms, but the conceptual terrain has remained the same. I work out of the same place of strangeness, foreignness, and racial melancholy/mania. I have had a lot of variation in my approach and form which I think comes from my thinking of intangibles like ideas, styles, and histories as material. I’m always trying to work from the inside and outside at the same time. Subjective truths. Objective realities.

The Republic, 42.5 x 108 inches, Ink stamped bananas and Acrylic Paint on paper with cut negative spaces and pinned to wall; Back painted blue and red.

You often work with unique combinations of materials, such as bubble wrap and dry rice, and including recent work with clear, acrylic paint skins that are stretched and attached to the wall with pins. How do you go about finding these new materials and using them in such different ways?

I often select materials, and lately, imagery, that I associate with the language and rhetoric surrounding Asian immigrants and foreigners. I use those materials to call upon tropes and associations that speak to perpetual foreigner scripts, yellow peril, and model minority myths through the language of abstraction and painting. In my mind, those chosen materials exist as anchor points where various lines of meaning overlap and calcify into a solid thing. At the same time, the way I work is more process-oriented. So it is as if I gather material--things from the world that carry meaning/significance as well as physical art-making material like paint--and let them interact in a non-hierarchical way. Things like bubblewrap, wiggle eyes, rice, etc. are how I materialize these nebulous concepts from the atmosphere into something tangible that I can work with my hands.

The piece Foreign Founder is comprised of hundreds of tiny banana stamps on paper, with many areas delicately and painstakingly cut out by hand. Can you tell us more about the thought behind this piece? What is the significance of the banana symbol, which appears frequently in your current work?

I grew up in the suburbs of Flint, Michigan where much of the economy was tied up in the American auto-industry and fears over Asian competition still lingered. Growing up, terms like “Asian invasion” could be heard in the media and casual adult conversation. I remember a teacher, when talking about China, casually said that there were so many people there that dropping a bomb on them would be doing them a favor.

Foreign Founder along with The Republic are the firsts in a group of works that uses the sheer quantity of bananas to mimic and mock the language of disease and military invasion that is often invoked when talking about immigrants to stir up xenophobic reactions. I stamped out bananas to show quantity, an anxiety inducing overwhelming quantity, in colors cheerfully bright to the point of aggressive. I stamped them out individually and cut them carefully by hand to create variation among them.

For me the banana is something both irreverent and pointed. Yellow on the outside and white on the inside, “banana” is pejorative shorthand for Asian-Americans to imply lack of authenticity and/or racial betrayal: Neither Asian enough nor American enough. It’s something I grew up with and still hear today. But in thinking of the banana further, I saw that the symbol of the banana goes beyond the Asian-American community. The idea of the banana calls up legacies of exotification, capitalism, imperialism, and colonialism--as well as a slapstick joke.

Untitled, 18 x 24 inches, Acrylic paint on paper cells and thread embedded in acrylic paint skin and pinned to wall by threads

Much of your work incorporates this intense and intricate labor to create the desired effect—from hand-cutting elements to carefully applying dots of acrylic paint with a chopstick to achieve a detailed, dot pattern and texture on the surface of your paintings. What role does labor play in your practice, both in the actual motion of repeating the action, and conceptually?

In its repetition, it’s how I communicate with the painting, stay in touch with it, and stay inside it. There’s an aspect of call and response: Marco. Polo. I’m always asking: what do you want? What do you need? It’s how I get to know the painting. I understand it more, I feel it more, I love it more. Process is how I also think through the concepts. In the labor, in working with my hands in construction and sometimes cycles of construction/destruction, I’m manifesting thought into something concrete and vice versa.

Conceptually, I associate labor with immigrants not as the iconic perception of foreigner as dangerous, destabilizing taker, but as the flip side--foreigner as hard worker/ social contributor. I’m a child of immigrants. Hard work is part of the narrative of how we survive.

What is your approach to your studio practice? How much time is allocated to ‘play’ and material experimentation and how much for the actual production? How much is planned and how much is intuitive and spontaneous?

For me experimentation is often bound up inside the production. Usually something, an idea, an object, an action will niggle at me. The experimentation is me chasing the rabbit down the rabbit hole, trying to understand what this thing is, what this thing means. Sometimes it goes nowhere, but the hope is, if I keep working at it, keep laboring, I’ll find the important thing, the necessary thing. Art-making is very much an act of faith.

In addition, you also work quite a bit with painted paper. What keeps you coming back to paper as a primary material?

I’m attracted to the lightness of paper. There’s something about it that could just blow away. Its commonness keeps a piece from becoming too monumental, too precious. It is facile and tactile. It’s portable. There’s the way it can hold a mark, a text, a doodle, or a painting. Even in its tearing, visually you can parse what happened and you can hear the sound it made.

I also have a lot of associations with paper. Most of the Korean decorative artworks my parents had in the home were traditionally styled works on paper or incorporated paper. When I looked at these pieces, I felt a connection to a familiar elsewhere that made me feel I’d come home.

Pattern and texture appear often in your paintings. Can you talk about your relationship to texture and how this ties into the themes in your work?

I often use texture to generate a gut reaction in the viewer. When we encounter texture with our eyes, we still feel it. I want to talk to the viewer on multiple levels. I want to engage the brain and the body, feeling and thinking. With touch, associations you have with the texture come quickly. I want the viewer to want to touch. The textures I create are often inspired by food. It makes the work feel both familiar and strange. It can bring out a sense of foreignness from within.

You travel frequently around Europe which is amazing benefit of living in Italy. How does this travel affect your work and practice?

As artists, we are always actively looking and absorbing the world around us. When I travel my synapses are firing and mentally dialoguing with the world around me. I see possibilities, potential, and so many ideas come to me. In travel, we have these opportunities, these moments, to see outside ourselves and see our own conceptual frameworks. When I travel, I see the things I accepted as background, become foreground.

What’s coming up next for you?

I’m attending Vermont Studio Center and am excited about the opportunity to meet and make work around so many other artists. I am excited about immersing fully in the art-making process and engaging in art dialogue. There, I will be preparing work to show in Bologna’s Art City and Art White Night event in January as part of Bologna Arte Fiera. I’m also honored and delighted that coming out winter 2020 my piece, “Bite of the Medusa,” will be featured on the cover of brilliant legal theorist and race scholar Anjali Vats’ book Color of Creatorship: Intellectual Property, Race, and the Making of Americans. It investigates the historical and contemporary relationships between copyright, trademark, and patent law and the articulation of (white) citizenship. And finally at the beginning of 2020 I will return to Korea, and right after, I will travel to both US and Italy, a unique moment where the places that make up my engine will all be fresh in the mental foreground and converge in my creative space.

Thanks so much for taking the time to talk with us!

To find out more about Nancy and her work check out her website at nancykim.net