Spotlight Artist: Math Bass

Installation view, Newz!, 2021. Murals of La Jolla, 7766 Fay Avenue, La Jolla, CA. Photo credit: Philipp Scholz Rittermann.

Math Bass in conversation with Marcus Civin

October 7, 2022

if i could sing you back: a performance with Math Bass & Eden Batki Henry Art Gallery, East Gallery. Saturday, March 05, 2022, 1:00 PM — 3:30 PM. Photo credit: Jonathan Vanderweit.

The Los Angeles-based artist Math Bass received a BA from Hampshire College and an MFA from the University of California, Los Angeles. Solo exhibitions include clown alley at Tanya Leighton Berlin (2022), Desert Veins at Vielmetter, Los Angeles (2021), a picture stuck in the mirror at The Henry Art Gallery (2021), Crowd Rehearsal at the Jewish Museum (2017), and Off the Clock at MoMA PS1 (2015). Their work is in museum collections across the globe. Bass likes this description that appears on the Tanya Bonakdar Gallery website: “Over the past decade, Math Bass has developed a lexicon of symbols in the series Newz!—letters, bodily forms, architectural fragments, animals, bones—arranged in a variety of scores, each symbol an empty space of meaning, filled in by the context in which it finds itself. Repetition of these symbols, rather than codifying them into one solid signification, exposes the difference at the heart of each iteration; there is always a gap in meaning, something unnamable left out of and left over in the viewer’s reading—a jouissance. It is this gap in the symbolic where Lee Edelman states queerness lies—not as an easily categorized liberal identity but as a process of unmaking and undoing that leaves (gendered) subjectivity as we know it in question.”

Marcus Civin: So, Math, I’ve noticed that your new works are oil paintings.

Math Bass: During the pandemic is when I made the shift. I’d been painting with gouache on raw canvas for a good seven and a half years, and I developed a very particular way of making images that left no room for error. Because I was working on raw canvas, if I made a mistake and got paint on the canvas, depending on how much paint and where it was, I would have to scrap the thing and start over. It’s funny how you’ll start making something a certain way, and then it becomes how you do something. In retrospect, I could have saved myself a lot of grief and time if I had just been a little more flexible. There was something about the way that the gouache absorbed into the canvas. It had this luminous quality because it was lots of thin layers. It kind of glowed in a certain way. I became attached to the pigment on that material, but it was time-consuming. Every line I would delineate first with a barbecue skewer cut at a bevel. I had assistants working with me. It was many hands on one painting, and in a way, I felt alienated from the process over time.

MC: Did you say barbeque skewers?

MB: Yeah. They were cut at a bevel like a pen quill. I worked for another artist who used barbeque skewers to apply masking fluid to paper to mask images. I went from working for that artist to working for myself, and when it came time to make sharper lines, I was like, “Oh yeah, barbecue skewers.” I would never have thought of barbecue skewers otherwise. I could only use one for so long until it got dull, and I’d have to cut a new one. I tried to find the best barbecue skewers. What held up the best for whatever reason? Then, right before the lockdown, I went to the desert with my partner to watch my friend Jennifer Bolande’s dog while she and her partner went to New York for an opening. I was supposed to be in the desert for ten days, but we rented another house and stayed for two and a half months. When it was time to go back to LA, I didn’t want to leave because I was very cozy at that point. I went back to my studio, and some paintings were mid-completion. I went to work on them. Barbecue skewers: I was like, “I can’t do this.” I had ordered a small set of oils when I was in the desert, thinking I might try it, but it was intimidating. A friend of mine, another artist, Alex Chaves, was staying for a while at my studio. He would give me lessons. He was like, “Ok, let’s order you the paint. Let’s order you the brushes.” He showed me how to mix the paint.

Installation view, Hammer Projects: Math Bass, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, September 29, 2018-February 17, 2019. Photo credit: Brian Forrest.

MC: I love that. Covid school.

MB: Yeah, Covid school. Alex was like, “Lean to fat! Always paint lean to fat!” He’s an amazing painter, one of my faves, and also a really good teacher. You know, the first year was so hard. Particularly the first six months. It was a humiliating experience to go from feeling proficient at something to feeling like a beginner and not having control, which is what I desired, but it was not easy.

MC: Was oil paint faster? It can also be slower in some ways. You have to wait for the paint to dry.

MB: Time is embedded in the process. That’s something I love. I love that it takes some time to dry. It doesn’t take that much time, but it’s enough that you don’t have to rush through.

MC: It seems meaningful perhaps that you got into a more tactile medium when people were afraid of touching.

MB: That was part of it. I couldn’t go from being isolated in lockdown—unable to see people, to touch people—and then have a process of artmaking that allowed for no error. It was too much restriction. There’s pleasure that I’m finding in making this newer body of work that I didn’t always experience before. I would take a lot of pleasure in having a finished painting and image that resonated for me, but the actual process of making was slow and stressful sometimes. Oil painting allows for error and surprise.

Gemini VI, 2022. Oil on linen. 50 x 52 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo credit: Brica Wilcox.

MC: I wonder if working with oils changed your approach to imagery and abstraction.

MB: Right now, I’m working explicitly with the language I’ve developed. I feel like people refer to the work in terms of abstraction a lot, and I don’t think of it as abstraction. I think of it as a language.

MC: I wasn’t sure if I should say the word abstraction.

MB: It does make sense to say it. My work aligns with a lot of work that we would consider abstract, but to me, it’s not that. I think of my work as a language. The forms I use have multiplied over time. I’ll take a fragment of a previous form, and that fragment becomes its own part of the alphabet. I have a whole library on the computer including every letter I’ve made. Every time there’s a new letter, it goes into the alphabet. It started originally where I had maybe four or five of these letterforms or characters. I would draw them on graph paper. Then, I started taking the photo documentation of my work, isolating every form, and putting them into Photoshop. Photoshop allowed me the freedom to play around and generate more forms. Now I compose forms digitally. All of the forms essentially come from the four or five early forms. One of the forms that I use a lot is a speech bubble that became a pink cloud. I think about composing things like making electronic music. I’m into arranging sounds and working with voice. I’m into the poetics of language, singing, and monastic chanting. A lot of the way I think about composition is creating language that has tension. Think about a sentence that pulls in two directions. What are the possibilities? How can letters form this sentence, and what kind of paragraph can result? There is so much potential. I will get into these rhythms where I’m obsessed with a particular grouping. Certain works I’ll see before I compose them. Other times, I start from zero and ideas surprise me. My friend Karl Haendel and I are doing a trade. I made him a painting that I’m calling Karl’s Junior. He was like, “I want it to look like a Math Bass.” It was fun to paint because I was pulling from a color palette and forms from the beginning of my practice. But, I included other forms that didn’t exist at that time, so the painting is a conflation of the present and the past. It has a crocodile smile. That becomes a face, and then it falls apart.

Through The Fog, 2021. Oil on canvas. 38 x 40 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton. Photos by Dan Finlayson.

MC: Do you want to talk about clown alley, one of your most recent exhibitions that took place at Tanya Leighton gallery in Berlin?

MB: I wanted to paint a clown, but I didn’t want to paint a clown. One day, I was shifting around parts of my alphabet and made a clown. I started to paint brick walls. The brick wall is the backdrop for standup comedy. It’s such a cliché; it’s almost a readymade. This was also the time when the US was building a wall. And “Build That Wall” was this disturbing slogan for The Right. But then, the brick walls in clown alley were yellow. Usually, when I’m working on a body of work, I’ll start with one or two images. But, I never really know what’s going to happen, so it’s about moving from one image to the next and waiting for more to present itself. Every show is a mystery for me at first, like finding a piece of string sticking out from the dirt. I pull it and pull it and see what’s at the end. I’m following this line. Not a straight line by any means, and it’s definitely underground. Chunks of dirt fly out as I pull! My process is pretty intuitive. Though, in the execution of a painting, there is a lot of structure. Once I know what I’m going to make, sometimes I deviate, but often I don’t. One of those brick walls I didn’t intend to envelop it in fog. That was just something that happened.

MC: You had chairs filled with fruit in the gallery in Berlin?

MB: They were seats from boats. They were small enough that they almost felt like elementary school chairs. They were piled up with apples, pears, and oranges. I was thinking about binaries, the non-binary pear, and body shapes. Are you an apple shape, or are you an orange shape? Apple shape or pear shape? Apples and oranges! The chairs were very slowly spinning on motors. Two of them were spinning clockwise, and two of them were spinning counterclockwise. They were cranking the show.

I feel like a clown sometimes, or I feel like I have to occupy this space where I’m the entertainment, singing and doing a jig for my supper. Growing up, I was such a bad student. I was so bad at school that I had to be a clown. That was what I could do. I found out later, after I came up with the clown alley title, that a clown alley is a sort of backstage area where the clowns convene before they come out, a space between the tents where clowns can get changed. I’ve always been into the backstage or offstage space. While you’re performing, if there’s a moment where you go offstage, it’s a private moment. A little reprieve. Maybe you’re with your friends, and you give a little, “Yes, we’re doing it,” and then go back out. It’s just as magical to be behind as it is to be in front.

At The Henry in Seattle, I created a performance to open the show. I started behind this black, pleated curtain about thirty feet long. I was walking back and forth behind the curtain, and then I started singing. I came out from behind the curtain and activated different architectural features I had built. When I exited through the curtain, I tripped this motor, a robotic device that simulated my movement. My movement was replaced by this machine. It gave the impression that there was something or someone walking behind the curtain as if someone else might come out onstage, like when there’s a spotlight on, and someone is stumbling to find the opening in the curtain. That’s a comedic moment. It’s pretty funny. I think about Jack Goldstein’s short film, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1975), which repeats the lion roaring from the beginning of MGM films.

MC: I admire how you involve humor in your work. I also wanted to ask you about love. I was writing down a list of questions to ask you, and I just wrote down the word “love.” I don’t know why exactly. Maybe because sometimes there is love behind painstaking detail, or in the community that develops among artists?

MB: Love is everything. As far as my relationship with community post-pandemic and as I get older, I would say it is shifting. It’s sort of a loner moment for me. But, as far as love and the devotional practice of making art. That is part of the practice. It’s full of love. It’s full of time. And, I hope that it’s generative and the love can be felt. Love is relevant, for sure.

MC: Can you talk about how you got to where you are, working with galleries, for example?

MB: Relationships are the most important thing. Galleries are a personal relationship and a business relationship. It’s important to find galleries that are invested in your longevity as an artist and not just making hasty decisions to move your work. I have been surprised by people it took a while to warm up to, but then they were in my corner and really wise, pragmatic, and great advisors. As far as getting a gallery, I have no idea! I would say, if you are really needing to get a gallery, you should get a bunch of friends together and clear space out in someone’s living room and have a show and invite all your other friends. If you like a writer or admire someone else’s work, and it’s not going to be too out of left field, you could be like, “Hey I’d love to take you to lunch. Or, can I get you a cup of coffee?” You have to feel it out because if someone is busy… But, if there is some connection, I think you can be brave and say, “I love your work.” Be generous with yourself and try to offer love genuinely. I came up in my early twenties, barely out of college, with a group of artists in Chicago, and we weren’t looking at the art world, we didn’t know what it was, but ultimately it was being part of that kind of community and related dialogues that got me to this point in my life. You can’t grasp too hard for the thing you want, but you have to figure out how to live it.

MC: Is there anything you wish people would ask you about your work or a way you wish they would talk about your work?

MB: I feel like my identity is embedded in my work. My work is very trans. What that means to me is that it has to do with mutability and multiplicity. It’s nonbinary. It’s not “A” or “B.” There’s this indeterminate space that I’m interested in. I embody that. I’ve been embodying it for twenty years, which is a long fucking time. I don’t talk about being trans all the time because it’s very much in my work. It’s not on the face of it. It’s baked in.

And then, it’s not abstract! There was probably a time when I didn’t know what language to use, and I did default to using the word abstract. I’d like to figure out more language to use because I feel like when something isn’t exactly representational, or realistic, it falls into the category of “abstract.” But, I think there’s space for more.

To find out more about Math Bass check out their Instagram.

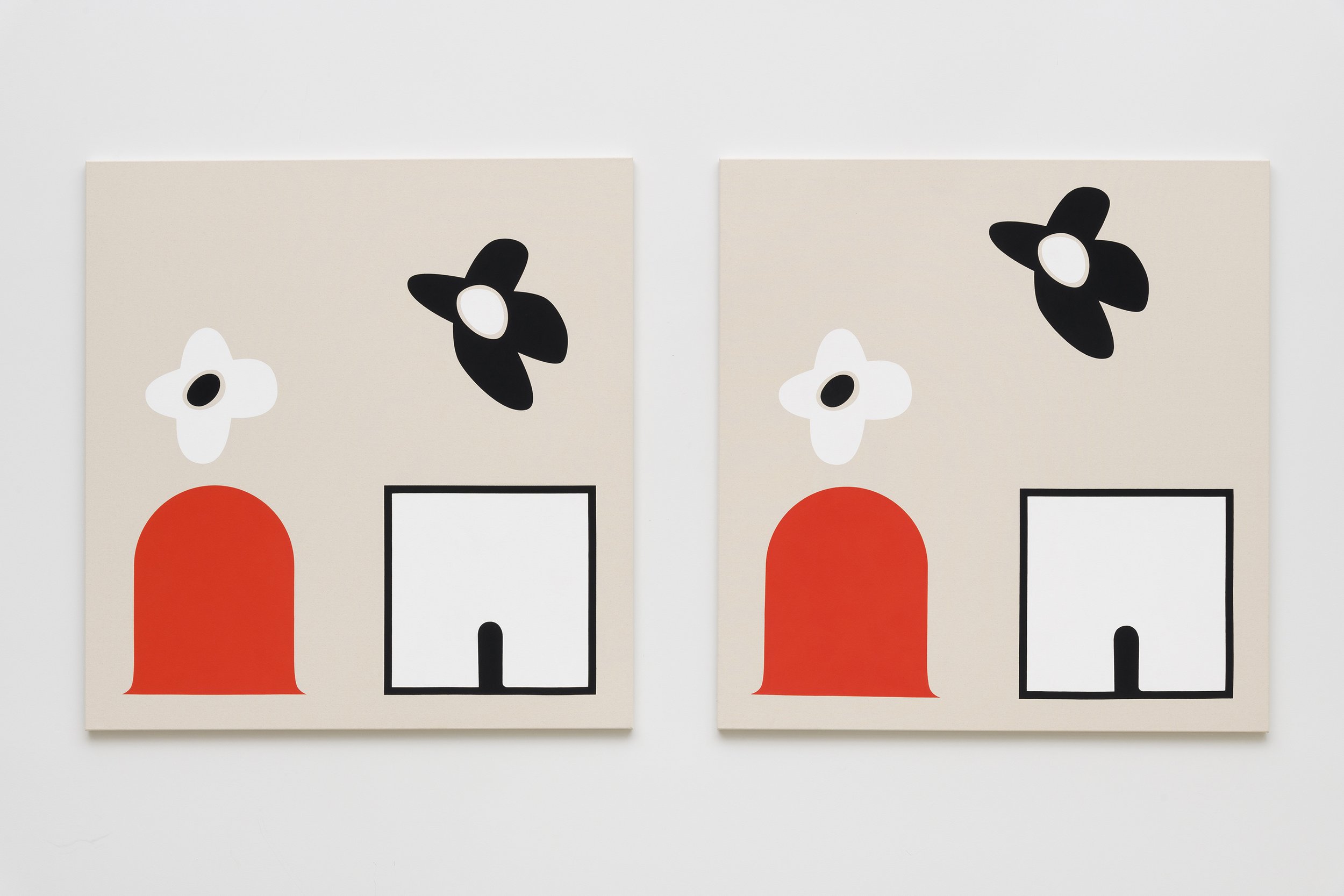

Newz!, 2019. Gouache on canvas. Diptych; Each 52 x 50 inches. Signed and dated on verso. Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo credit: Jeff McLane.