Gaku Tsutaja

Gaku Tsutaja was born and grew up in Japan. She obtained BFA with honors from Tokyo Zokei University of Art and Designs, Tokyo, Japan in 1998. In the same year, she was granted Research Fellowship at Center for Contemporary Art Kitakyusyu (CCA), Fukuoka, Japan, and spent two years as a resident artist. She has lived and worked in NY for 11 years and is currently a MFA candidate at SUNY Purchase College, year of 2018.

Tsutaja’s works have been shown in numerous exhibitions including; The Kingdome of Kitai, Ulterior, NY (2017); Make a World, Nitehiworks, Kanazawa, Japan (2012); First Look 2010 Emerging Artist Series New Tale for Our Age, Visual Arts Center of New Jersey, Summit, NJ (2009); Independent Drawing Gig 3, Quartair Contemporary Art Initiatives Exhibition Space, Hague, Holland (2007); Password, Center for Contemporary Graphic Art, Fukushima, Japan (2004); Blind Date, Kunsthallen Brandts Klaedefabrik, Odense, Denmark (2002). She was also a part of an artist collective, Gansomaeda, and exhibited works at Yokohama Triennale, Yokohama, Japan (2005), CHANNEL_0, Akiyoshidai International Art Village, Yamaguchi, Japan (2004), and other exhibition projects.

Tsutaja is represented by Ulterior Gallery in New York, NY.

Gaku working in the studio

Q&A with Gaku Tsutaja

Questions by Emily Burns

Hi Gaku! Can you tell us a bit about your background and what motivated you to become an artist?

Hi, Emily! I was born and raised in Japan. During my undergraduate study in Tokyo Zokei University, Great Hanshin Earthquake and Tokyo subway sarin attack by Aum Shinrikyo both occurred in the beginning of 1995. Facing on this state of panic triggered by two separate disasters, I was questioning myself about what to do as an artist. My idea was to generate a conversation in Japanese society surrounding these issues. This is also when I encountered Ilya Kabakov’s work, and was inspired by his narrative format of work. This Russian artist’s work was my first experience engaging with contemporary art. My experiment was to find a function for contemporary art in Japan, an area where the majority of viewers have no experience with Western contemporary art. After BFA, I participated to the residency program, CCA Kitakyushu in Japan, and found an artist collective named ‘Gansomaeda’ with a colleague artist there. The main concept of our five-year activity was to show a satire of Japanese artists who occupied the position between Western art and Japanese society.

I moved to the United States in 2006. Here, my immigrant experience, cultural difference, language problems, race issues and economic condition made me curious, lonely, and feel the need of connecting with others. As a Japanese, I realized that a symbol which is familiar to me can have different meanings or values in different contexts. I establish connections between the familiar and the unknown, embedding a narrative structure within a multimedia format. My purpose is to uncover multiple possibilities within a symbol, to break through the existing story line and my own imagination. This excites me as I discover unexpected connections and developments within the story. My intention is to stimulate the viewers’ imagination, by showing only parts in the whole, allowing them to notice the warp that connects layers of race, ethnicity, class, politics and ideology.

Can you talk us through the stages of planning and making an artwork of your choice, in terms of the evolution of the idea to the finished piece?

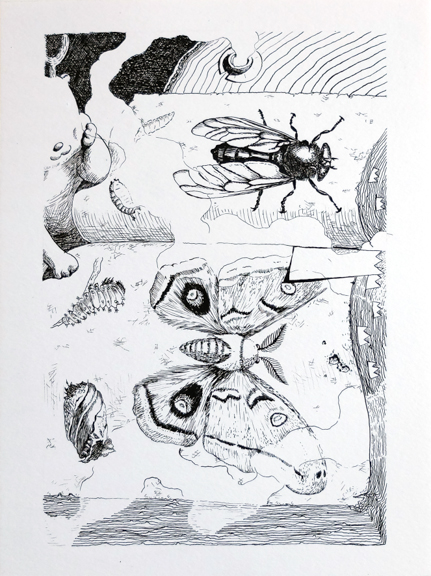

I just struggle. It is very complicated and difficult to organize my brain. I have a lot of ideas, and just start with a lot of drawings that capture my ideas. Some are narrative drawings and some are planning drawings for sculpture or other media. Drawing is important as the starting point to figure out if the idea will go well or not. I just try to draw all the ideas I hit on. I love this process. My sketchbooks are filled with parallel worlds of a project which would be selected as a figure at the end.

Are there any overarching themes that you keep returning to in your work?

I am currently working on epic projects that involve animal protagonists—dog, cat, cow, pig, hen, rooster, ostrich, mole, beaver, groundhog, parakeet—which I depict as creatures without eyes. The blind animals constitute small societies within the culture at large, enacting and embodying its struggles and violence. The work reflects an apocalyptic world which was started in my response to the Tohoku earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear power plant meltdown in Fukushima, Japan in 2011. This environmental issue is still a big negative influence in Japan (for the world, too) and I have been working on it with researching the history and events related to why we are having this problem now and how we can solve this problem including avoiding similar mistakes in the future.

You recently had a solo show at Ulterior Gallery in New York where you exhibited many different works, including ink drawings with brightly colored paper frames. Can you talk more specifically about the work in the exhibition as a whole?

The title of the show is “The Kingdom of Kitai” which is a fictional nation with the model of 1960’s Japan. The story was constructed based on my father’s memory and documents. He was a civil engineer in post-WWII Japan who helped with the nation’s postwar recovery and development as well as the negative impact upon the environment including the construction of the nuclear power plants.

The audience can experience the narrative of this kingdom through a 9-channel sound installation with found objects, two sculptures and 12 drawings. Each work is a part of the whole. The sound installation is 48-minutes long. Nine non-human characters such as Kettle, Pickax, Central-Control-System, Mountain, Turbo-Sazae (turban shell), Helmet, Water, Decorative-Paper-Ball, and Crystal act as gods narrating the storyline in which animals are struggling for a dream project. In the sculptures and drawings, the audience can find the protagonists are moles, beavers and groundhogs as the civil engineers.

The gods’ story in the sound piece and the animal’s story in the drawings have different endings for a story; the former talks about the dream tunnel project which was not completed; the latter shows the completed celebration scene. Two sculptures give the viewer different entrances for the work. One is a symbolic entrance signboard, which is usually set in the entrance of the construction site to let others know who are in the site and who hasn’t come back from the site yet by turning their name tokens, and it is an important log for the workers’ life line. Another is a complicated structure of a miniature mountain sculpture, which shows a tunnel, a mysterious scene with Turbo-Sazae, who is one of nine gods, and a disaster scene, which is narrated at the end of god’s story as a prophecy.

Each piece has different aspect of a world. Audiences puzzle out the parts to imagine what is going on there and add their own imaginations and ideas.

Can you tell us more about the ink drawings specifically?

My comic language style of drawing was started around 2007. Most topics were satire for my hardship in New York. I was combining pencil, color pencil, marker, pen and anything I could use to draw. When the Tohoku earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear power plant meltdown in Fukushima, Japan in 2011 occurred, I went back to Japan and started to create the series called Daily Transform Comic, which proceeded a page per day. I showed the completed page immediately on the blog and some free comic stream sites at the end of the day. I wanted to observe myself and changed daily. The reaction from my audiences (most were my artist friends in Japan) encouraged and inspired my daily process and story progression. For drawing, it is important for me to work intuitively and catch the unexpected possibility. I tried to select the unknown way for the story, then found it led me to reach an interesting story. Currently, I have been using this method as a part of my projects.

You are currently pursuing your MFA in visual arts at SUNY Purchase College, in Purchase, NY. Can you tell us how your experience in school has influenced you as artist thus far?

With my language limitation in the U.S., I had been working in the realm of immigrants for 10 years to survive in NY. Then, I decided to apply to Purchase College’s MFA to reconstruct my life into the one as an artist. This program consists of only 15 MFA students for the first and the second years. We can receive a lot of advice from many faculties of artists and critics. Our conversation is concept-based as we are all working interdisciplinary. Here, I have re-contextualized my immigrant identity by clearly defining the cultural differences and connections, misunderstandings and unexpected emotions in our conversations as a clue. When I say “immigrant identity,” I mean my position that is placed on borderline between two worlds, not my identity as a foreigner. Also, reading well-selected theories in the art history class gave me a deeper understanding of Western art, and knowledge of the history of other borderline artists’ struggles and experiments in the U.S. as well as in an international art context. My work has developed in this academic environment with a sense of clarity, and it has been meaningful step for my practice.

In the past you have made very large-scale, colorful paintings on unstretched canvas. Do you still work in this way? If not, would you ever come back to this scale? How does this work related to your current work?

I have a strong bond with this traditional media as I started as a painter although I stopped painting when I was in undergrad. I left it because I did not believe painting was an effective language to generate conversation in Japanese society where the majority of audiences are not familiar with Western art. When I moved to the U.S. in 2006, I was so surprised at the fact people are enjoying and talking about paintings. Here I witnessed the power of painting and restarted the challenge of using the painting format. I selected the mural size as I like the painting as a monument for everybody. Art is for me the medium to communicate within a Western context, and painting is the most typical one which is still difficult for me. Recently, I haven’t worked with this format, but for me, “format” is a translation language for the idea, so it could be used again for the right topic or necessary within the combination of other formats.

What have been some of the biggest influences on your life and your work thus far?

Although I wrote about it already, the disasters affect my work. One is the Hanshin earthquake, and act of terrorism by the cult, Aum Shinrikyo in 1995. The other is the Tohoku earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear power plant meltdown in Fukushima, Japan in 2011. Whenever I face with such big events, which shook my home country, I had to rethink about my role as an artist in contemporary society.

Who are some of the artists that you look at the most often or most recently?

Ilya Kabakov made me to start the narrative format. He is still a great model for me as an immigrant artist who left his home country but makes work about his homeland.

Huang Yong Ping’s ideas are closest to mine. He is also an Asian immigrant living in Western world.

What type of studio scenario do you need to get work done?

Surprise, bravery to break through my own imagination, and satire for myself.

Has there ever been a book/essay/poem/film/etc that totally changed or influenced you? What are you reading right now?

I am a big fun of Lars von Torier. His work and spirit grabs my heart and blow my brain all the time. Bertolt Brecht is always my teacher. I was knocked down by “The Threepenny Opera.” Haruki Murakami’s structure of parallel worlds influenced my work. Hayao Kawai (Japanese Jungian psychologist) helped my life. His study and practice were between the original Jungian method for Western people and Japanese, and his book saved my distress many times. Kunio Yanagida’s work of folklore is important for my narrative. And Yoshikazu Ebisu is my favorite cartoonist who reminds me that shame is ok.

Recently, I read Homi K. Bhabah and Susan Buck-Morss.

Their texts made me believe that my effort can affect the world. In the U.S., it had been difficult to have a positive view on my own effort because of my own experiences and what I witnessed as an immigrant over the last decade. Eighty percent of my view was negative as a human, and also as an artist who tried contributing to make a better world till I read these texts. I read these texts in a history class in Purchase College MFA. Reading these texts with my American classmates and professor also made me feel a possibility for the future.

What do you listen to while you work? Is this an important part of being in the studio?

I rarely listen to the music when I work. I love music, and some music inspires me a lot. But when I work in my studio, I prefer it to be quiet. The only sound in my studio is as a part of my sound piece or video work.

How important is the place where you live to your studio practice? This could include geographic location, city, neighborhood, community, etc.

New York inspires me as an artist. I have been living in Elmhurst for four years now. This neighborhood consists of various immigrants, not so many Japanese, but I feel comfortable in this hybrid working-class culture. Most people have a constant life with family, speak two languages between generations, some in hard conditions of life. This environment keeps me thinking about what and how I do as an artist for society. At the same time, my partner is living in the Hudson Valley. I sometimes visit him and can spend time in nature. As I grew up in Tokyo, Japan, the energy of the city inspires me basically, but it is great to have some time in nature to be conscious of how the city can give a negative influence on the human condition.

Do you have any other news, shows, residencies or projects coming up?

My thesis show will be at Richard & Dolly Maass Gallery in Purchase College in May 2018. I have already started to work on the new project called The National Museum of Parakeet History in which monk parakeets act as an immigrant metaphor and repeat the memory during the WWII. All the elements of the museum are composed of and work with any media, including SSN and a website to create this ideal for the institutional model. This is an ongoing project. Please follow the official Instagram of The National Museum of Parakeet History.

The National Museum of Parakeet History

Official Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/monkparakeets/

Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with us!

Thank you.

To find out more about Gaku and her work, check our her website.